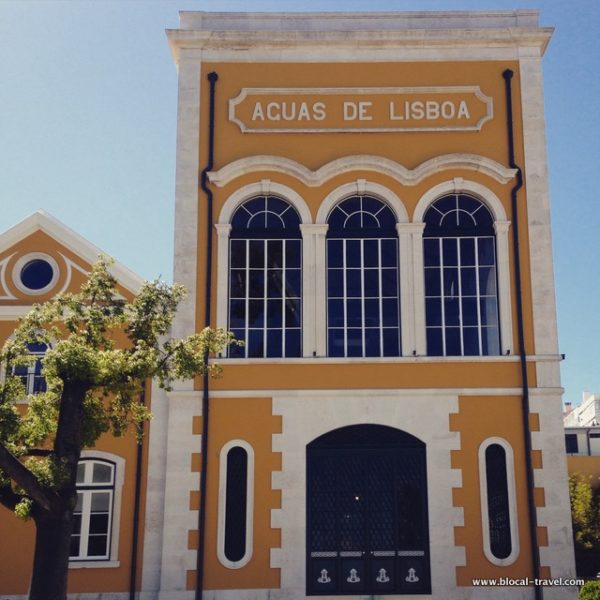

The Lisbon Water Museum shows the history of the public water supply of the city. Held by Lisbon’s water company EPAL, the water museum consists of four spaces scattered throughout the city, four buildings built between the 18th and the 19th century that are part of the historical heritage of the city and -therefore- inscribed into the UNESCO’s world heritage list. But, unlike any other UNESCO site, they aren’t crowded with tourists!

Do you want to explore Lisbon with me?

info on the lisbon street art trip

Save the dates: May 8 – 12

Lisbon Water Museum > The Águas Livres Aqueduct

Moving around Lisbon, I couldn’t help noticing the massive 18th-century aqueduct that runs for 19 kilometers throughout the city.

Planned under King João V (1689 – 1750), the aqueduct wasn’t completed until a century later. It was possible to build it through the levy of a tax called the ‘Water Royal’ duty on essential goods, and in his book ‘Journey to Portugal‘ José Saramago writes that there used to be a plate honouring the efforts of Lisbon’s people, a plate that -25 years later- the Marquis of Plombal replaced with one that doesn’t mention the people’s contribution to the construction of the aqueduct.

A National Monument since 1910, the Águas Livres Aqueduct was a vast system for collecting and transporting water using gravity, running along the same trajectory of the old Roman aqueduct and using the water springs of the Águas Livres, which are near Sintra.

Its waters were used for human consumption until the 1960’s, but the aqueduct remains a remarkable example of architectural engineering for its length (almost a kilometre) and especially for the heights of its thirty-five arches, one of which is the largest ogival stone arch in the world.

The water carried by the Aguas Livres Aqueduct was conducted through an emissary network of five galleries about 12 km long; one of these galleries, the Loreto gallery, can be partially visited, but unfortunately when I learnt about this opportunity it was too late to book one tour.

Moreover, while getting closer to the aqueduct to take some pictures, I discovered a very nice hood called Campelide.

Campelide looks like a fishermen village; the houses are small and colorful, and the aqueduct is majestically embedded into the ‘village’.

Lisbon Water Museum > The Mãe d’Água das Amoreiras Reservoir

The Aguas Livres Aqueduct feeds into a beautifully designed reservoir known as the Mãe d’Água (Mother of Water), which was the principal water reservoir of the city.

Completed in 1834, nowadays the former reservoir is an intriguing underground temple to water, an ample space used for events and exhibitions, subtly designed to recall a church and therefore suggest the holy nature of the space.

When I visited the ‘temple of water’ the ongoing exhibition (‘Whispers. Water reflexes in Portuguese tiles‘) was about 18th-century water-themed azulejos, the traditional Portuguese tiles.

Following the exhibition, I wandered around the cavernous structure covered in marble, which develops around a deep cistern of transparent water, where the reflection of the massive vaults and columns overlaps the broken image of the staircase starting from the tank floor.

The same staircase leads behind the waterfall fountain and, further on, to a panoramic terrace overlooking the neighborhood of Amoreiras, another area of Lisbon I liked a lot.

Lisbon Water Museum > The Barbadinhos Steam Pumping Station

Built between 1880 and 1928, it served as a steam pumping station for the last reservoir of the water transported using the Alviela aqueduct, a new aqueduct built from 1871 to 1880 to meet the demand for water after Lisbon’s population growth.

It gets its name from a monastery that used to be in the place of the station, which was inhabited by Franciscan friars wearing long beards, ‘barba‘ in Portuguese, hence the nickname ‘barbadinhos‘.

The museum, featuring a series of pieces belonging to the company’s collection, is located inside a former industrial building, and so here you can also admire a piece of Lisbon’s industrial archaeology and, especially, the old steam machines and respective pumps dating from 1880, which were in use until 1928.

It’s a pity that very few locals know about this UNESCO site, as I noticed when I got lost in the area and asked for directions. But, at least, that gave me the occasion to wander around the hood of Poco do Bispo, a very genuine area of Lisbon.

Lisbon Water Museum > The Patriarcal Reservoir

During my week in Lisbon, I kept walking through this elegant square, called Principe Real, but until my last day in town I didn’t know what was underneath it. From the Principe Real garden, in fact, all I could see was an octagon-shaped, iron fence around a pond.

This reservoir, built during the 1860s and deactivated at the end of the 1940s, was designed to supply the downtown area of Lisbon, and it was aimed at regulating the pressure between the Arco Reservoir and the piping system of the city’s downtown area.

Entering the space, the first thing that struck me was the system of pillars and their different widths; they support the stonework arches, which in turn support the cupolas.

As a whole, the water museum is an interesting way to get to know Lisbon. The former steam pumping station is impressive and the Mae d’Agua das Amoreiras reservoir is a magical place where the noise of the town is suspended. The aqueduct is majestic, and the Patriarcal reservoir is literally a hidden gem right underneath Lisbon’s touristy surface.

Plan your trip to Lisbon with my Lisbon Google Map!

Do you want to explore Lisbon with me?

info on the lisbon street art trip

Save the dates: May 8 – 12