I spent a week in Stigliano researching the Appartengo Festival, catching the participation and enthusiasm of the residents, documenting Argentinian street artist Milu Correch’s work in progress, and discovering the murals and public art that have been produced since 2017.

All of the artworks produced during the five editions of the Appartengo Festival are site-specific; they originated in an art residency during which artists explored Stigliano and its surroundings, while mingling with locals and learning from them about the history, culture, and the local legends.

The outcome is an outstanding collection of murals and other works of art that locals recognize as something that speaks both to them and about them. I’ve grouped Stigliano’s murals and art installations in four major themes and aligned them along a single storyline that illustrates the many different facets of this magical place.

- Appartengo Festival | Street art about local myths and legends

- Appartengo Festival | Murals and installations about witches and esoteric knowledge

- Appartengo Festival | Street art and public art about Stigliano's history and its people

- Appartengo Festival | Murals and public art about religion

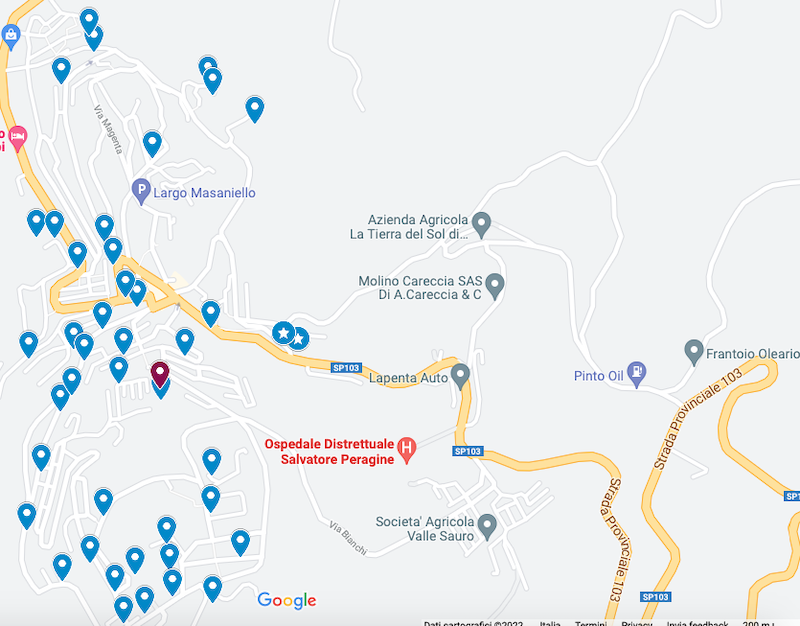

- Stigliano Murales Map

Appartengo Festival | Street art about local myths and legends

Many murals and art installations produced by the Appartengo Festival tell the story behind the local folklore. The most popular of which is the legend of the dragon, which is also featured in Stigliano’s coat of arms. As the myth goes, a terrible dragon terrorizing the local population was defeated by a warrior.

In many ancient myths a dragon represents a natural disaster; following this tradition, Ericalilcane painted a multicolored dragon destroying the village houses, much like the landslide did in 2014. As is often the case with his murals, the fairytale traits of Ericailcane’s animals share the scene with the urge of local issues he gathers by connecting with the community where he paints.

For Barlo, however, the dragon symbolizes the Agro River, which was reclaimed in the 15th century by the will of a count (the hero of the legend), although the actual job was obviously done by the local farmers. “Non al conte, ai contadini” (“Not to the Count, but to the farmers”) is Barlo’s tribute to the local rural knowledge, which is about to disappear, neglected by the new generations.

As a long-time politically committed street artist, Nemo’s represented the mythological fight in a controversial mural denouncing oil drilling in Basilicata.

A more traditional image is the reinterpretation of Stigliano coat of arms in a mural by Ufocinque, which is part of a series dedicated to local heraldry that the artist is painting throughout Italy.

The Stigliano coat of arms is also reproduced in the installation in terracotta by local craftsman Giovanni Sansone next to the entrance of Saint Anthony Church.

His brother, Mario Sansone, is also an expert craftsman and his sculptures in ferrocement are scattered all around Stigliano.

When I visited his studio, Mario was working on yet another “Mnocidd” -who, according to a local legend, is the wandering soul of a child who dies without baptism. He will install it in the Mandarra Park, among its fellows.

The legend of the Mnocidd is also the story behind the mural painted by Nicola Alessandrini, featuring several objects that, as clues, tell us more about this mythological figure; that it prefers to play his pranks at night or at dawn, and that the only way to make him powerless is by taking off its hood.

When night falls in Stigliano, there are more mythological figures to be afraid of, like the werewolf painted by Piskv.

Appartengo Festival | Murals and installations about witches and esoteric knowledge

Many regional legends are about local witches, the infamous witches from Basilicata that have inspired the Grimm Brothers. It’s no mystery that the scariest witches of the German siblings come from a 17th-century book (“Lo cunto de li cunti”) written by Giambattista Basile, who drew inspiration from Basilicata’s magical landscapes, mysterious events, and eerie folk legends.

Among these scary witches is a witch that can be spotted only in Stigliano. Her name is Mandarra, and she is an exceptionally tall woman who wanders around the village at night, strangling humans with her very long legs. The Mandarra is the protagonist of the mural painted by Gio Pistone.

When I was in Stigliano I closely followed the artistic process of Argentinian street artist Milu Correch, whose recent work is all about the witchcraft trials in Europe and what is left of such ancient, mystic knowledge. Her mural, though, is in the nearby village of Montalbano Jonico, where Milu Correch inaugurated a spin-off of the Appartengo Festival.

Read also: One Week with Milu Correch

Local esoteric knowledge is also at the core of Borondo’s installation “Reminiscence,” which is visible only at night. Above the female figures engraved in the glass panel, the Spanish artist represented some objects traditionally used in witchcraft, like the home protectors aimed at keeping the evil’s eye away.

Appartengo Festival | Street art and public art about Stigliano’s history and its people

Representing the female family members who are no longer living in Stigliano, Borondo’s installation is also about the many families that, since the 1960s, have left the village, dramatically bringing Stigliano from 12,000 inhabitants to barely 3,000.

Depopulation is not limited to Stigliano but a widespread phenomenon throughout the region; the nearby village Craco turned into a ghost town, albeit a very touristic one. Stigliano, however, with its cinemas, restaurants, and many administrative buildings was the main village in the valley and many elders I met there wanted to share stories with me from a time when Stigliano was lively. They reminisced of neighborhood summer night dinners with the distant laughs of children playing in the streets, a playful atmosphere well-exemplified in the bas-relief by Giovanni Sansone titled “Nascondino” (“hide-and-seek”).

The Appartengo Festival itself is born as an attempt to fight depopulation by bringing art, art lovers, and artistic synergies to Stigliano, and it’s no surprise that a theme so heartfelt by the population is also showing up in many works of street art throughout Stigliano, like this stunning mural painted by Nemo’s titled, “3, 2, (no)One.”

As a matter of fact, the depopulation of Stigliano began way before the late 1960s. Local poet Pio Rasulo already predicted this in a poem he wrote in 1961 (“Resteranno i corvi,” crows will stay), which has been transcribed by street artist Bifido on a wall beneath pasted-up photos portraying the local elders. Eventually, the paper will be consumed by the rain and fall away, making the prophetic poem surface from the wall.

We can actually trace the depopulation all the way back to the 19th century, when thousands of Italian families immigrated to America. This is the story of Jimmy Savo -mime artist, Broadway star, comedian, and “the world’s greatest pantomimist,” according to Charlie Chaplin- whose parents left Stigliano in 1888 and moved to New York. Jimmy Savo is portrayed both in a mural by Chekos and in a sculpture by Mario Sansone.

A more contemporary take on the same phenomenon is the wall by Leticia Mandragora highlighting that youngsters from Stigliano, who are missing opportunities at home, still nowadays have a suitcase ready by their side.

The snails by Giovanni Sansone are, instead, a metaphor for those who decided to stay, those resilient souls who live adhering to the earth and holding on to their house.

Staying isn’t a popular decision, which brings to the vicious circle of depopulation-downsizing. Cutbacks at the local hospital began in the 1990s, and today its mere existence is at risk, as highlighted by Daniele Geniale in a mural whose title can be loosely translated with “Gambling with healthcare is betting one’s life:” a “rock, paper, scissors” game between the resilient healthcare workers and those who keep cutting resources, even in a time like the pandemic when hospital capacity is crucial.

Even before the cutbacks at the hospital, Stigliano suffered for the shut down of the Antico Pastificio Sarubbi in the 1970s for reasons unrelated to its pasta production, which was actually going great: it employed more than 100 workers and its products were renowned as far as in the United States.

The importance that the cultivation of grain used to have in the local economy is celebrated in a colorful mural by Bastardilla and in two past-ups left by Bifido in the old part of the city.

Among many other difficulties that Stigliano had to face there are landslides, which are quite common in Basilicata, a region literally built on clay. Gola Hundun realized a powerful installation -named “Kintsugi,” after the Japanese art of repairing a broken pottery with gold, thus enhancing the breaks- in the site of the landslide of 2014. By recreating the natural flow with 480sqm of golden satin, Gola Hundun drew attention to the dual nature of water, which is essential to life but also very disruptive.

Both duality and the landslide are also at the core of Mino Di Summa’s mural “Terra d’Amare,” a “land to love” suspended in time and space, represented as a girl who protects herself from the landslide with one hand and, with the other hand, treasures and protects her land. Mino Di Summa’s mural is an invitation to take care and cherish what Stigliano has to offer, from its ancient tradition to street art.

Yet another homage to this beautiful land is Alessandra Carloni’s mural “Canto della Terra” (“Song of the Earth”): a surreal scene animated by one of her iconic characters playing the “cupa-cupa,” a traditional instrument of the region, while the dreamlike scenario exemplifies the need for awakening and renaissance.

A similar metaphor was intended by French street artist La Rouille in his Klimt-inspired mural featuring the sleeping beauty.

This hoped-for awakening evokes the human pyramid painted by Gods in Love as a metaphor of the Stigliano community coming together to overcome natural disasters and other adversities.

Next to resilience, another characteristic of Stigliano inhabitants is their warmth and sociability, very lovable traits that have inspired the abstract mural of French artist Nulo. The red and blue shapes symbolize France, while Stigliano is represented by the golden wheat-growing lands.

Appartengo Festival | Murals and public art about religion

Stigliano people are also very devout, so it’s no surprise that many artworks are inspired by religion. Once strong opponents of witchcraft and esoteric knowledge, nowadays religious beliefs go hand in hand with superstitious rituals.

Borondo’s second installation “Plan” is an homage to the old tradition of offering grain to Saint Anthony, the patron of the village, to secure a rich harvest next year. Honoring the farmers’ hard work and the sacredness of grain and land, this 8,000sqm installation presents elements that are very important for Stigliano people.

In fact, we find them also in a mural painted by Mino Di Summa on Saint Anthony Church, where the Saint is represented next to ears of wheat, which symbolize renaissance, hope, and future.

The old, wooden crucifix kept inside Saint Anthony Church inspired Kirill Vedernikov, a young artist from Russia at his first experience in Italy. As the story goes, this crucifix is responsible for a miracle that happened in 1656: it ended the plague with a flick.

Two more artworks imbued with religion and symbolism are those made by Luis Gomez de Teran, respectively the mural “Sacrificio celato” (hidden sacrifice) and the installation “Crucifragium.”

Madro Art turned a tiny old door into Jerusalem’s Golden Gate, a place of high significance for Christians, Muslims, and Jewish believers alike, to state that every humble door turns into a golden portal when it leads us towards our goal.

As for Appartengo and its goal of breathing new life into the local community, when opportunity isn’t knocking the festival is building doors.