At Nuart Aberdeen last year, I had the pleasure to help Carrie Reichardt mash hundreds of tiles into smaller pieces that—like the colours in a kaleidoscope made of life’s shards—would eventually tell two powerful stories on the walls of the Granite City. This year, after her talk had kicked off the Nuart Plus conferences programme, we sat down for a quick chat…

“What do you do?” Carrie asked demoralized, while putting away the videotape she had made for the interview. She had set her mind on specializing in Fine Art Filmmaking, but she just discovered that that particular degree was no longer attainable at Leeds University.

“We do printing, painting, and sculpturing,” they curtly replied.

“Give me a hammer, give me a chisel, and I’ll do Sculpture,” she declared.

Carrie never intended to be an artist, although she has been “making crafty stuff” ever since when she was a little girl.

Carrie Reichardt: “I was introduced to crafting when I was a child by my mom, who happened to be a fanatical knitter. She let me be as creative as I wanted: gluing, sticking, colouring, and all that.”

Her study of sculpture was almost entirely accidental, after an Art Foundation year at Kingston University (1987 – 1988) when she engaged in art therapy after being sexually assaulted at the age of 21.

Carrie Reichardt: “Art has always been therapeutic for me. Even though I’m known for public speaking now, I couldn’t say anything for a long time. I would never have dared to do public speaking, never. I was terrified of it! I even had tonsillitis and all kinds of throat problems before figuring out how I could express myself through art.”

When searching for her creative voice, Carrie found a natural speaking voice that fit her well. What motivated her to speak on stage was her political activism; she wanted to talk about her friends who were in prison, as she couldn’t stay silent at the sight of human rights being violated. Over the years she associated her name and her art to several causes: prisoners on death row, the Angola 3, women rights, and several other noble causes fighting injustice.

Carrie Reichardt: “I don’t think artists should be socially engaged. Rather, us as human beings must be socially engaged.”

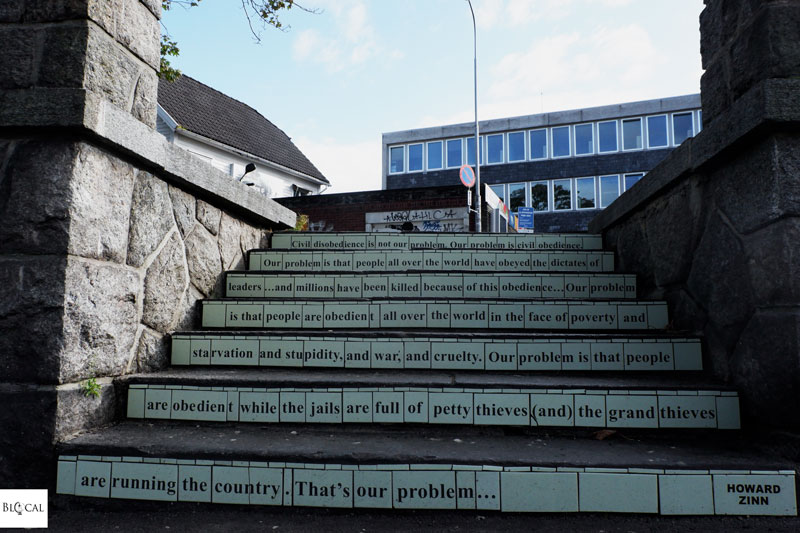

Indeed, she proudly represents a movement—which she calls “craftivism”—that counts several fellow artists using craft and art as protest. Even though her public art has taken different shapes over the years, Carrie has always given voices to the overlooked communities by creating works of art that truly engage. Having witnessed how art has been her own therapeutic salvation, Carrie committed herself to doing community mosaics for more than 10 years at places such as schools and hospitals.

Carrie Reichardt: “However, I did all that community art under a different name. I’ve always struggled with my own ego; I didn’t dare be an artist. It took me years to put my name to something.”

In fact, Carrie has had a long journey of feeling comfortable with calling herself an “artist”.

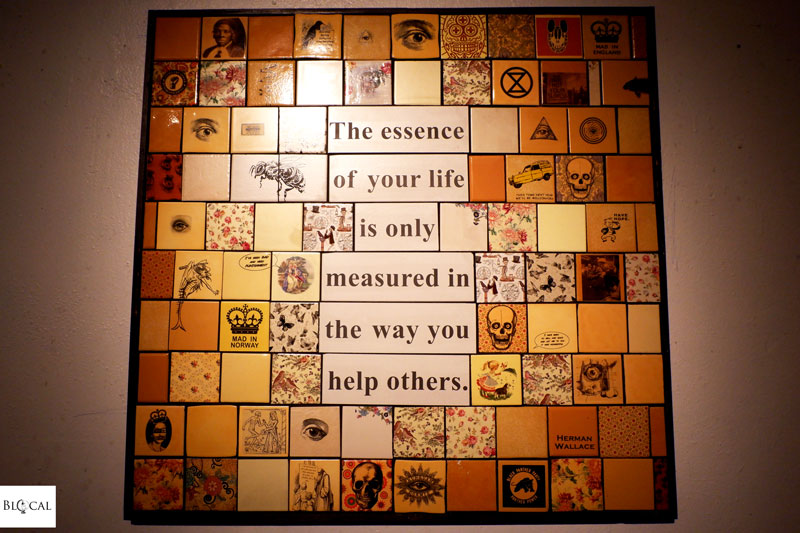

I had such low self-esteem about my ability to draw and paint, because I’ve always compared myself to other ‘artists’. Only now that I’ve spent more than 15 years doing this craft it kind of validated it for me. Today I do feel confident that I do crafts in a skilful way, creating something that is totally different from traditional mosaics through the technique of collage and by printing on tiles. I haven’t seen anything like that before, which makes me proud of doing it, proud of having created a new language for mosaics.

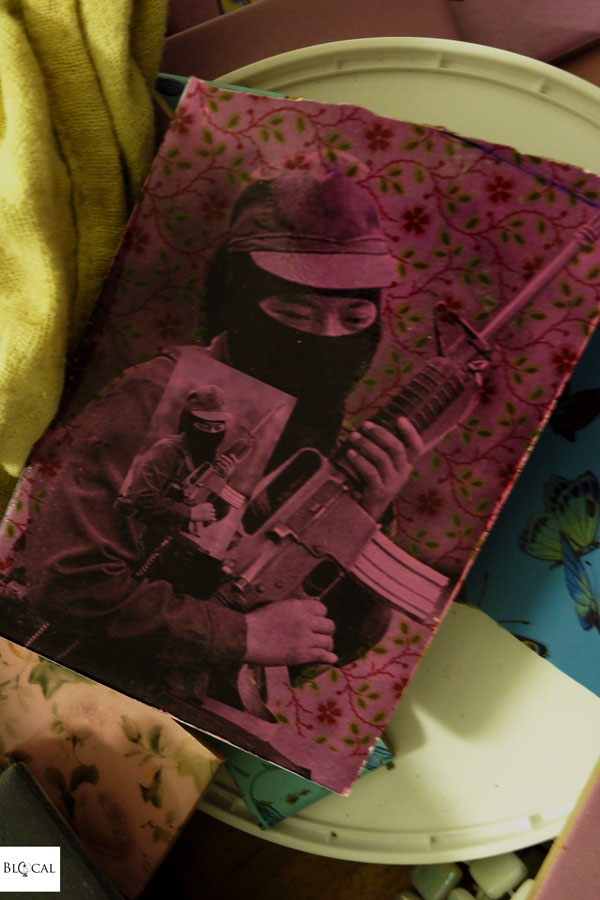

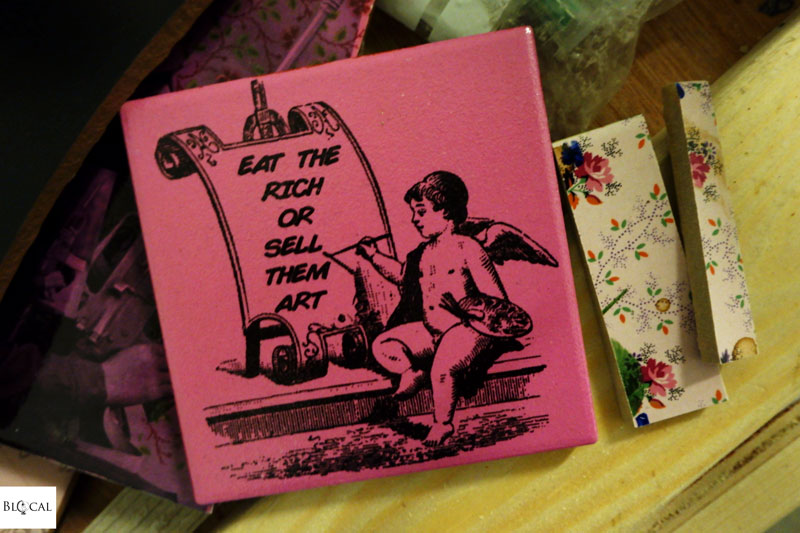

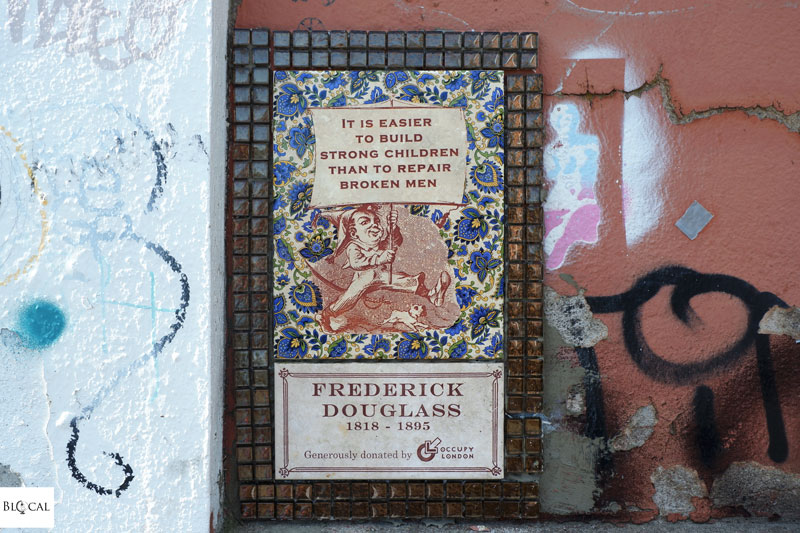

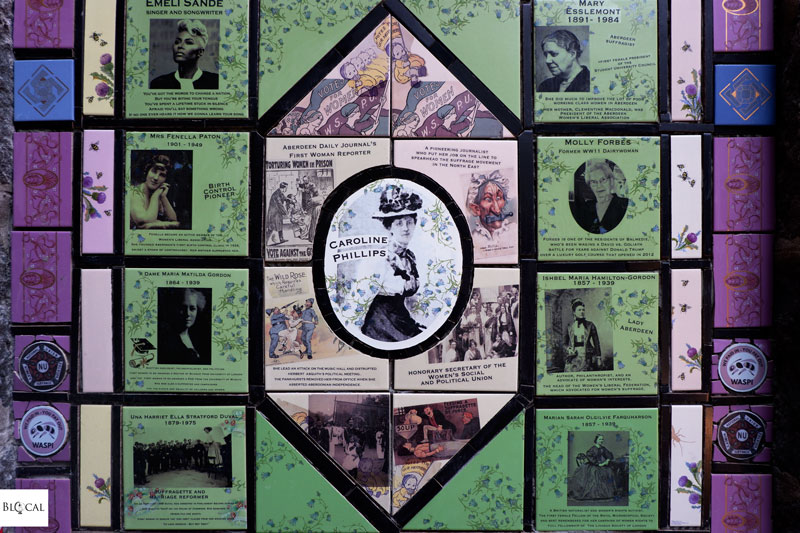

The alphabet of Carrie’s new language is made of vintage floral and kitsch, skulls and eyeballs, royal and religious crockery, cheeky slogans, and political statements. Each tile is a small, anarchic artwork on its own, yet the final piece is more powerful than the sum of its vibrant parts.

Another fundamental aspect of Carrie’s practice is the massive research that comes before assembling a mosaic.

Carrie Reichardt: “I dig deep into the archives of the city and I work closely with the local community by engaging groups of people who can add their thoughts to the historical research. I like the idea of us creating a ‘ceramic tapestry’ together, because I’m very conscious of the permanence of what I do. I want to be site-specific and really make my piece about the elements of the local history that I discover through my research and by talking to the local people.”

Nuart Aberdeen 2018

This exact type of research occurred when she was invited to create two public artworks during the Nuart Aberdeen street art festival in 2018.

Nuart Aberdeen 2018

Carrie Reichardt: “When I first came to Aberdeen they took me to this great archive, which was incredible: it’s one of the best archives in Scotland. They showed me papers that were 800 years old -very fascinating, but visually I couldn’t really do anything with them.”

As she later happened to mention she was interested in witches, they showed her a single, yet extremely comprehensive article on a dark page of Aberdeen’s history. Carrie’s mosaic was set to be located in front of Nicholas Church, where local witches in the past have been tied up in a circle and held there during freezing winter months for weeks.

Carrie Reichardt: “I’m pleased I did it, because you won’t see any public art celebrating the achievements of women. Rather, we are bombarded with this over-sexualization and constantly judged upon our looks.”

Nuart Aberdeen 2018

Nuart Aberdeen 2018

Nuart Aberdeen 2018

Carrie was invited to Nuart Aberdeen 2018 after having taken part in the original Nuart Festival, which happens in Stavanger every September. Nuart 2017 was Carrie’s first street art festival, which she landed quickly after having set her mind on becoming a street artist.

Nuart Stavanger 2017

Carrie Reichardt: “After a wonderful experience of making public art mosaics in Chile in 2014, I began thinking I wanted to reposition myself as a ‘street artist’. I could see the reach that my friend ATM Streetart got through it, and that street art was becoming the new religion. I was simply joking about it with my friends, though. I hadn’t even attended a street art festival before! Then one day, totally out of the blue, Nuart’s curator, Martyn Reed, sent me an email to invite me to the Nuart festival in Stavanger. He knew my work because he saw my mosaic truck at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. This is something admirable about Martyn; he doesn’t necessarily invite artists who have a history in street art, he gives a platform to all the artists he truly believes in.”

Nuart Stavanger 2017

Aside from bringing together artists doing all different types of artwork—yet all sharing a similar desire to see art being used as an engine of change—Martyn Reed also set up a section of the Nuart Festival—called Nuart Plus—where different speakers talk about the different nuances of street art. Among this year’s artist talks, there was one done by Carrie Reichardt.

Carrie Reichardt: “Nuart Plus’s conferences are great. Susan Hansen is very good at reaching all kinds of people. She is an academic, but she does understand that too much ‘academic’ might be monotonous, so she spices things up by bringing together interesting people from different fields. I love to attend all the Nuart Plus’s talks, because I always learn so much. They are truly inspiring and allow the public to see things in context by hearing different opinions of people from all over the world.”

Back in Aberdeen as a Nuart Speaker, Carrie also checked out the second piece she put up last year: a local homage to Everyday Heroes. The piece was moved to a new location by the same artists who worked with her last year, and Carrie couldn’t be more proud of them taking ownership of the artwork.

Nuart Aberdeen 2018

Carrie Reichardt: “Residents are truly engaged with the Nuart Aberdeen Festival, either as volunteers or as active participants. This is one of those places where people in the streets stop you and say they love what you are doing on the walls of their city. You can really see how engaged everyone is with it. It was evident last year when I came here to do my research and—after that—when I was working in the streets, I can see how the festival has grown bigger and better! Often when events are council-founded, the output might be sterile. This, however, is contrary to my experience with the Nuart team. I can say that they are still prepared to take risks and allow artists the freedom to do what they want.”

Nuart Aberdeen 2018