Raised in southern Italy, Greg Jager was active on and under the streets of Rome at the turn of the millennium. After being part of the second generation of graffiti artists in Rome, he began spraying abstract, conceptual pieces in public spaces (and, more recently, in his studio), investigating the close relationship between art and architecture.

Although it was already a widespread phenomenon internationally, graffiti was fairly obscure in southern Italy in 1996, when Greg Jager began writing his graffiti name.

I remember first seeing graffiti in American movies that had nothing to do with graffiti culture; iconic movies from the ‘80 that my older sisters were watching on TV, on channels like MTV and DeeJay Television. American pop culture from the ’80s was permitted with New York’s underground movements: Michael Jackson got his moves from breakdancing, and both Crazy Legs and Mr.Freeze had a cameo in the popular movie Flashdance. The music video for ‘Rapture, by Blondie, featured Fab Five Freddy, the legendary artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, and the graffiti writer Lee Quinones, because singer of the band, Debbie Harry, was a good friend of all those people.

Greg Jager

Brought to Italy through music, TV, and cinema, New York’s underground culture conquered the imagination of a young Greg Jager who, through his contagious enthusiasm, dragged several friends into his first graffiti crew back in the mid ’90s.

The first graffiti I’ve ever seen was a huge piece reading “POSSESSIONE”. It was red, yellow and green, very “reggae style”. I was 8 and I guessed it was about heroin, which was widespread in those years. Years later, I found out it was the name of a “posse” (Italy’s collectives made of rappers, raggamuffin singers and graffiti writers, which were a thing in the 1990s). Members of the Possessione spent their summer vacation in my hometown and left that graffiti behind. That visual code planted something in my mind, something that blossomed 6 years later.

Greg Jager

Aside from writing his name, Greg was fascinated by the culture behind graffiti. He was getting a hold of fanzines, which were rare and hard to find, especially in a small village in southern Italy. Nevertheless, he was an assiduous reader of many of them, from “Aelle”, which was popular nationwide, to the ones produced in his region, like “OnéSound” by ASC Crew from Cosenza. Moreover, for two summers in a row (1999 and 2000), Greg organized a graffiti and music jam that brought to his seaside village many graffiti artists from all around the country.

My best memories are related to our hospitality: writers and musicians were sleeping on the beach, under the stars, smoking weed and playing music. After the jam, we built a D.I.Y. sound system on the beach, creating a situation that was very similar to reggae parties. I made many new friends and my efforts were appreciated by older, more experienced artists. For a 17-year-old, that gave me great satisfaction at the time.

Greg Jager

Creating connections between writers and working with different crews is a role that stuck with him even when Greg Jager moved to Rome in 2000 to study Design at IED Academy. Greg never fully committed to one single crew (despite his passionate activism with ARF and KIDZ), but he enjoyed painting with many different people, like POISON, REPS, ZETAL, TROTA and many others. Most of the time, he was painting with BRUS, whom he met shortly after he moved to Rome.

Over the years I’ve changed several crews, but I’ve always been in a duo with BRUS. We have been painting together for 20 years and even though he now lives far away, we still are good friends. I will never forget our messy weeks in New York, in 2004: that experience has radically changed our mentality and opened us to new influences. We first met at Circolo degli Artisti in 2002, at a graffiti and music jam called ‘Da Bomb’. BRUS was painting there, showing something awkwardly similar to a NY-’80s style. That blew my mind, since it was something completely different from everything else I could see around Rome at that time, the so-called Roman Style.

Greg Jager

Back then, graffiti in Rome had a very marked aesthetic (the Roman Style), which was developed by the TRV crew and then formally adopted by most of the writers throughout the city. Greg Jager, instead, stepped into Rome’s graffiti scene as an outsider, hence his style with strong, unique traits.

I think growing up in a little village was both a bad and a good thing. If I were from Rome, I would have found everything ready, without having to work hard for getting what I wanted, like I did.

Greg Jager

The year Greg moved to the Eternal City was a particular year for graffiti in Rome. After the Jubilee of 2000, the city wanted to show off an immaculate image. Metro trains were cleaned throughout 2001, and so a big part of the massive legacy of Rome’s first generation of graffiti was erased. At the same time of this total reset (or ‘the big buff’, as we call it in Rome), there was the attack on the Twin Towers in New York, which immediately meant larger and heavier controls on both metro lines in Rome. Sneaking into the tunnels became harder and Rome’s trains were running untouched once again. The time had come for a new generation of graffiti writing.

There is an exact moment marking the beginning of the second generation of graffiti writing in Rome: a whole-car reading “Mister Poison,” with the twin towers depicted in between. POISON painted it all by himself, in vivid colors. It must have taken him three to four hours. He put into everybody’s face his typical letters, which were almost italics; they had nothing to do with the Roman style. It was something so massive that it became the fundamental divide between the first and the second generation of graffiti in Rome.

Greg Jager

POISON grew up in a small city near Rome. Like it happened for Greg Jager, growing up away from the capital and its ubiquitous graffiti aesthetic (the Roman style) allowed POISON to bring to Rome a different way of painting letters: a cleaner, almost glossy style that had no relation with the roughness of the Roman style.

Still, in 2003, PANDA and TROTA painted an end-to-end train reading “Italian Graffiti,” which flaunted white, italics letters and a red, three-dimensional outline. In the following years, many other writers added to the variety. Inspired by EUROPEAN STYLE and that much impactful whole-car, writers from Rome in the 2000s began developing their own unique style.

At the same time, the scene itself was becoming less sealed off with the arrival of the internet, which made comminglings of different styles more common.

We were meeting online, in a mIRC chat, which was a website that was around since the late 1990s, even before MSN and Myspace. There was a channel called “#writerz” and it worked like a discussion forum, so it was possible to chat with people that weren’t in your circle. It became our meeting place, and I definitely enjoyed the opportunity to meet likeminded people, albeit virtually.

Greg Jager

The 2000s were also the years when writers shifted from simply documenting their activity to telling the story of graffiti to a wider audience. In graffiti culture, one of the main reasons for painting trains is that trains make graffiti travel across the city. Through blogs like “Strada Nove” by Pietro Rivasi and the many documentary movies self-produced by different crews – like “Un gioco da ragazzi,” “Ghetto Blaster,” “Dirty Hands,” “Nero d’inferno,” and many others- a graffiti piece could now “travel” faster and farther than a train. These independent movies were also a way to document an aspect that is at the core of graffiti: the adrenaline-fueled action.

I remember when POE set his mind to shooting “Ghetto Blaster,” a documentary about the ARF crew showing epic actions on trains in Rome, Milan, Naples, Madrid, and Barcelona. He was always bringing his camera into the tunnels and he was shooting everything, like other writers were doing at that time. Those years were not just about painting, but also about telling the story of a new generation of graffiti writers in Europe.

Greg Jager

Along with the internet, another groundbreaking event of this decade is the diffusion of interrail travel, which allowed graffiti writers to travel all around Europe to paint different metro systems at a very low cost. As such, Rome suddenly became the graffiti paradise of Europe, as it was one of the few cities where graffiti would travel all around without being cleaned. Writers were coming from allover Europe, which resulted in a variety of styles that built up the layered scenario of the Eternal City.

Between 2004 and 2009 Greg still was a main point of contact within the national and international network of graffiti writers, who often were his guests when visiting Rome. His place next to Tiburtina station became a meeting point for the graffiti scene.

I was living the life of my dreams. I shared an apartment with a fellow graffiti writer, we were sketching at home through the evening and then painting together in the night. We hosted writers from all over Europe, and travelled ourselves to other cities with a car full of spray cans. Everywhere I went, I found someone willing to host me. In the summer, we were all travelling to Salento to stay at RATS’ beach house. There I met writers from all over Italy, and even from abroad. I still cherish that feeling of being part of such a great community.

Greg Jager

Sorry to interrupt, but… Would you like to read more graffiti stories? Then join up Blocal’s newsletter and get them straight into your inbox every 1st of the month!

The early 2000s were the dawn of Rome’s street art movement, pioneered by artists in the likes of Sten & Lex, Lucamaleonte, JBRock, Diamond and Hogre. They were working illegally, with methodologies that were very similar to the ones used in graffiti, but with a fundamentally different goal: starting a visual dialogue with passersby, as opposed to communicating with their peers through an inside code.

The phenomenon that is commonly called “street art” was nothing more than a new way of approaching the public space. In those years, widely used graphic software, such as Photoshop and Illustrator, allowed artists to digitally design images that could be easily reproduced, which is to say quickly turned into posters, stencils, stickers, etc… Personally, I was very fascinated by the work of “Why Style”, the collective founded by some members of TRV Crew. Their artistic approach was completely different from what is commonly called “street art”, and especially from what I could see at that time in the streets of Rome. The best example of it is the exhibition “Romamsterdam” at Museo Trastevere. Curated by Cecilia Nesbitt, this collective exhibition featured Why Style artists (Pane, Joe, Nico, Stand and Scarful from Rome) next to Amsterdam’s legends in the likes of Yalt, Delta, Zedz and the Machine duo. This exhibition pushed me to investigate new visual languages through which I could evolve and stay true to my background.

Greg Jager

Another exhibition that marked Greg Jager’s artistic path is “New York Minute” (MaCro, 2009). This exhibition boasted artists such as Barry McGee, Steve Powers, Ara Peterson, and Dash Snow.

On that occasion, Josh Lazcano, Barry McGee’s friend, made the huge silver piece reading JOSH that you can still see next to the museum entrance. He climbed onto the scaffolding that was there for some renovation works, and he did it over a couple of nights; first the silver and, on the day after, the outline. And then, when the scaffolding was taken off, everybody could see what has now become an iconic piece of illegal art in Rome.

Greg Jager

In 2011 Greg Jager, who now works as a graphic designer and art director, was asked to join the team of “Outdoor Festival,” one of the most important urban art festivals in Rome.

I was wary of street art exhibitions and festivals because I heard people talking about them and none of these people really knew what they were talking about. Suddenly, the same people who thought that graffiti was ugly and an act of vandalism, now they were liking street art and supporting it, without knowing that some of the artists they supported were ‘vandals’ in the first place. Moreover, curators and other gatekeepers of the old art world were providing an incorrect reading of the phenomenon through fictitious explanations from their outsider’s perspective. This is why the actual protagonists of Rome’s writing scene have always kept at distance from the system that was arising around “street art.” So when I was invited by Francesco Dobrovich to collaborate with the NUfactory team to organize the first edition of Outdoor Festival (which was curated by Christian Omodeo), I recognized the opportunity to create bridges between art, graffiti and the public. In my opinion, Christian Omodeo has been the first curator I met who truly understood the essence of graffiti writing.

Greg Jager

During the first three editions, aside from working on the graphic design of the festival, Greg Jager also managed a couple of side events that turned Outdoor Festival into a place for deepening people’s knowledge about the movement. With the same “research attitude” that made him look really hard for rare fanzines when he was a kid, Greg organized a massive exhibition of Martha Cooper’s photos (Outdoor 2013) and a presentation of Andrea Nelli’s book “Graffiti a New York” (Outdoor 2012).

Photo courtesy of Greg Jager

I see this presentation as the perfect metaphor of the evolution of the times. Published in 1978, this obscure book stayed unknown to Italian graffiti writers until the 1990s, when it became an important reference for the TRV crew and therefore for the establishment of the Roman style. Ten years later, Greg Jager was introducing it to the public of a cultural festival, thus legitimizing the fundamental role of Andrea Nelli’s photos and critical essays also in front of an audience of amateurs.

When I joined Outdoor, my goal was to offer the audience content that was authentic, content that was actually coming from the graffiti world and not something misrepresented by outsiders. I wanted to share my passion for research. In 2012 I had the opportunity to organize Andrea Nelli’s exhibition in collaboration with Domenico De Girolamo and its ‘Whole Train Press’, which was releasing the reprint of the book “Graffiti a New York”. Then in 2013 I wanted to carry on disclosing graffiti history, and so I invited Martha Cooper, the photographer who witnessed 50 years of graffiti evolution in New York.

Greg Jager

This passion for research is what has always pushed Greg forward, eventually bringing him outside his comfort zone. Inspired by avant-gardes from the 20th century, which attempted at making art independent from either the depiction of reality or the transmission of a message, the “post-graffiti” movement has spread across Italy since the 2000s, when several writers began pushing their letters toward abstract art while looking for their own way to be creative beyond the rigid rules of style writing. Each one on their unpaved path, they began experimenting with new styles and different mediums that would still fit their graffiti background.

After painting a whole-car with POISON in 2012 and organising two graffiti exhibitions for Outdoor, I took a break from graffiti. For my last piece, I wanted to write ‘Say it Loud’ after a James Brown’s song. That was my way to exit the scene. Writing graffiti as we used to do, with all the rituals, suddenly didn’t make much sense. Graffiti was no longer a counterculture and, at the same time, I had grown up and developed a vocation for a particular kind of aesthetics: the one that enhances oddities and does not please everyone. The time had come for me to move forward, to find new motivations.

Greg Jager

The Story of Greg Jager: The Road to Contemporary Art

Greg Jager began experimenting with something new around 2015 inside the same abandoned factories where he trained himself in graffiti lettering. From this moment on, his aesthetic research focused on the geometric composition of colors, lines, textures, and forms, which he drew from his background in design and illustration, but also from electronic music of the early 2000s. Most of all, he focused his aesthetic research on the relationship between shapes and architecture, thus deriving his minimalistic compositions from their own environment.

I’ve always wanted to be ‘honest’ with myself and with those who view my work. I don’t want my art to be merely entertainment, something purely decorative. I want it to have a relationship with its context, either in the public space or indoors.This is how I became aware of the relationship between graphic art, architecture and anthropology, which is at the core of work.

Greg Jager

His career didn’t take long to take off. In 2018, Greg was invited by Open House Festival to produce his first commissioned piece in the public space: an abstract mural whose vector lines and transparent layers are inspired by the social and architectural context around it: the modern architecture of the new Testaccio market in Rome.

Shortly afterwards, Greg Jager was contacted by Giorgio De Finis, the visionary curator of a street art collection in a former abandoned factory in eastern Rome (MAAM, which I visited back in 2013) and, at the same time, also the curator of Rome’s Contemporary Art Museum MaCro.

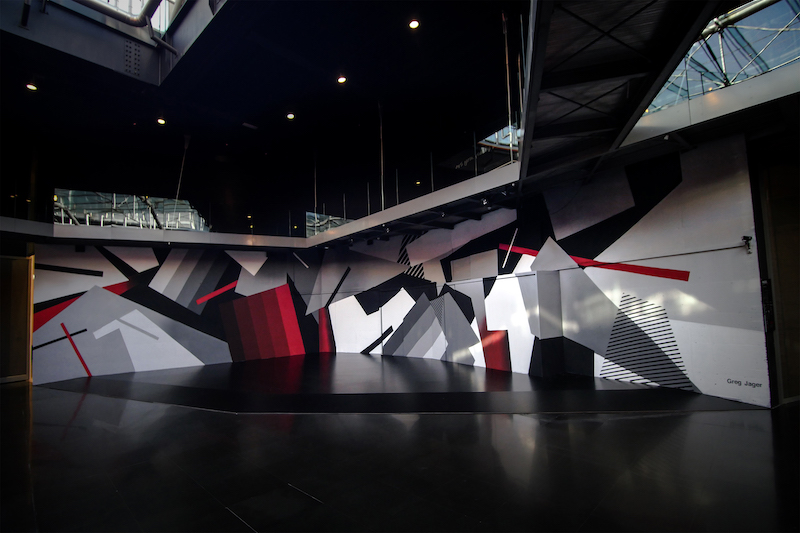

Giorgio made me do something way bigger than what I was looking for. When he saw what I was working on in the abandoned factories, he clearly told me: ‘now, you have to become architecture’ which is what I did.

Greg Jager

The huge mural piece at Rome’s contemporary art museum (MaCro, 2018) is inspired by the drawings of the architect Odile Decq, who designed the museum within a former brewery. Here, Jager’s abstract shapes make a dialogue with the sharp lines designed by the French architect as well as with the perceptions of the people bustling the foyer of one of the most popular museums in Rome.

I remember spending many days inside the museum when it was closed. I was there alone, looking for the most hidden and intimate elements of its architecture to turn into a graphic composition. I took several photos from which I extracted the most interesting elements, creating a dialogue with the lights and shadows of the place.

Greg Jager

Yet another site-specific mural based on a peculiar architecture is “Crossing” (Rome, Contemporary Cluster, 2019), where Greg Jager’s geometric shapes are juxtaposed to the Baroque frescoes on the ceilings of Palazzo Cavallerini Lazzaroni, serving as a metaphor for a wider stratification, both artistic and architectural, that has been going on across centuries in Rome.

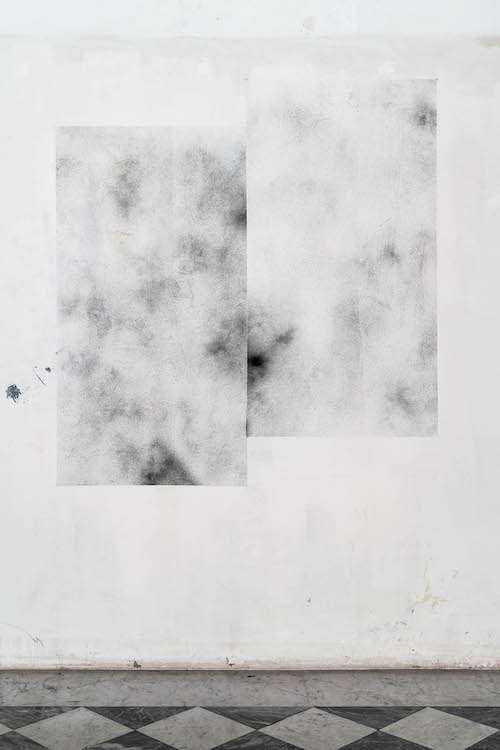

Still, in 2019, Jager began creating artworks in the studio, although he really committed to this new practice only recently. His first solo show (“Tempesta”, 206 Art Gallery, Bari – which is how I met Greg, albeit virtually… through a curatorial text by Amir Issaa a.k.a. China) only happened in November 2019. The challenge this time had been synthesizing his colossal, immersive murals into a compact format. Likewise, several Italian artists who share a background in graffiti, Greg Jager’s artworks are pervaded by an emotional tension that comes from the same place as the urgency of train bombing.

My mural production is at the intersection between graffiti writing and graphic design, and so it still exists within some sort of comfort zone. With these smaller artworks, I ventured into the unknown. These subtle artworks are somehow undefined, not obvious.

Greg Jager

This exploration brought him to the intimate, emotionally charged works he paints currently; a study that he notably deepened during the first lockdown.

Once the lockdown was lifted, Greg was invited to paint at Ragusa’s Festiwall, or its spin-off: BITUME. When I visited Ragusa in 2016, the curator of this urban art festival brought me into this vast abandoned factory where -back then- only three artists had left their mark. The project kept evolving under the radar throughout the years, hosting 25 street artists and eventually turning into an art residency, which Greg Jager attended in October 2020.

This experience provided Greg with the opportunity to investigate the relationship between art, anthropology, and architecture. Titled “Dismantle,” the resulting series of art interventions questions the economic model we derived from the massive industrial production of the prior century, exemplified in Ragusa’s vast industrial archaeology site. It’s an artistic interpretation that opens up to several future scenarios and the different ways we, as a society, must rise from our ashes.

The work I brought to Ragusa is philosophically inspired by thinkers like Donna Haraway, Mark Fisher, Timothy Morton. From being constructive my work has become deconstructive. Hence the name “Dismantle”. Not simply a name I chose to underline the charm of decay; it also represents an ethical approach to art: the idea of dismantling, deconstructing, stripping as an opportunity to rebuild a new world.

Greg Jager

His constant effort to unhinge eventually brought Greg Jager to dismantle mural art as well. What originally felt as a liberation from the rigid rules of style writing recently started to feel as an equally limiting box.

Why should I limit myself to painting? Art is conceptual, creativity and rebellion can take many different forms. My next step is to create art at the intersection between languages. I don’t want to have tunnel vision toward painting; my aim is to create ‘experiences,’ not ‘objects.’ I investigate different disciplines, from visual to performing arts, as well as the correlation between them. I want to create together with the audience, turning people into the protagonists of my piece. If I let them interact with something I create, the outcome of it (the “artwork”) will be unpredictable and somehow fluid. This is my vision at the beginning of 2021.

Greg Jager

Considering all the unpredictable turns that his artistic path has taken so far, I’m really looking forward to seeing how Greg Jager will keep pursuing his artistic research into the realm of Contemporary Art.

(…and if you are interested in it too, you can follow Greg Jager’s work on Instagram!)

Thank you for reading! Would you like to get more graffiti stories straight into your inbox? Then join up Blocal’s newsletter and see you there every 1st of the month!