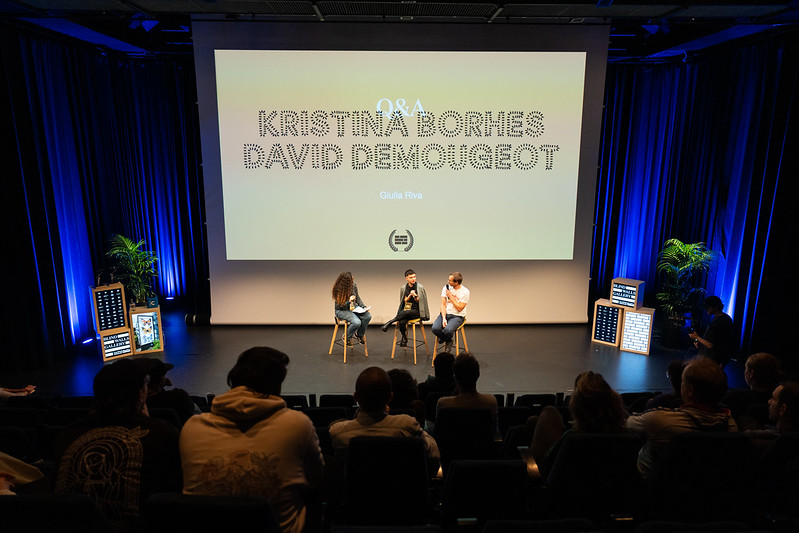

This isn’t the first time I have interviewed Kristina Borhes from MZM Projects, an independent duo of Ukrainian video artists focused on research and documentation of urban culture, but this time I did it publicly, on the stage of Blind Walls Film Festival 2023 in Breda, The Netherlands.

This Q&A followed the screening of Kristina and Nazar’s latest movie “Juste Ici et Pas Ailleurs”, focusing on the public art festival Bien Urbain (Besançon, France), one of the most genuine festivals out there. Our conversation brimmed with captivating insights, prompting me to transcribe it here for those who couldn’t be part of the film festival experience.

Giulia Blocal: Ciao! So, my first question is: how are you? Are you enjoying the film festival?

Kristina Borhes: Oh, nice. I’m doing pretty well. It has been amazing, I’ve seen a lot of movies. Okay, I’ve seen that one quite a lot. But other than this, everything else was very inspirational.

Giulia Blocal: I want to start with something that you already mentioned on Friday, because I see new faces in the audience. So, can you share your personal connection with street art and what motivated you to create a documentary about the Bien Urbain festival?

Kristina Borhes: Oh, yeah, I hope it will not take me 30 minutes, like my talk on Friday. So, basically, there’s a lot of things: I was studying political science, then I was a journalist, I was writing about cultural issues and social issues, but I was always interested in art on the street as a tool of communication. And then I went deeper; together with my partner Nazar, who is here but hidden in the audience, so together with him, we were working in an NGO, doing different things with the youngsters and the art. And then it came slowly to graffiti, then to street art, then to post-graffiti and all the different ways of communicating on the walls. So that’s the beginning, and then we started to work with street art festivals, to go deeper in the practices of some artists, and now the Bien Urbain festival.

Giulia Blocal: When did you first learn about Bien Urbain?

Kristina Borhes: I don’t even know! I was doing a lot of research in these topics, and the name of Bien Urbain kept coming up. I don’t even remember when I first encountered it, for many years it was the festival that everyone was saying “this one is cool, this one is truly genuine, this one is really different.” And the artists that were invited there, they were all my favorite artists. So I don’t even remember when it started, but I’ve been following the festival for many years, and saying “this one is interesting for me, I would love to go there.” And then through an artist, actually, we were introduced to David and we told him we wanted to do something with them. They were open to it, so that’s how it started.

Giulia Blocal: In your film, you highlighted several unique aspects of Bien Urbain that make it stand out globally, such as the focus on contextual art, the participatory approach and the social value. How did the festival’s distinctive values shape the way you approached storytelling in your documentary?

Kristina Borhes: We first had this idea to make the movie about the festival in 2019. From that time, the concept of the movie, in my mind, changed at least four times. Like, drastically changing. At the beginning, it was “oh, it will be like this and that,” and then “oh, no, it will be in a different way.” The more I discovered, the more archives I’ve seen, the more we spent time at the festival, the more the movie changed in my mind, and then at some point I just let it free. When I was discovering all these themes that I wanted to talk about -ephemerality, legality VS illegality, muralism or not- all this stuff, that was something that I was understanding during the process. It wasn’t there before, most of the things came up during the process. Doing the structure was the hardest part: to put these ten years of extensive, amazing practice, to put a lot of projects into some structure, to have a storyline, that was the hardest thing. But also the most rewarding one, because I really understood a lot after all these years of work.

Giulia Blocal: A similar question for David: considering the festival’s values and its perspective of the city as a playground, how does this approach affect the way artists engage with the urban environment?

David Demougeot: I’m not sure about the festival influencing the artists, it’s just that we let the artists do what they want, they can take their time and they’ll have a lot of people around to help them and to give them insight about the city. I always say that as an organizer, we are experts of our city and artists are experts of their art. And it’s this collaboration that leads to contextual projects. The artists we invite, when they work at home, they still do contextual projects. That’s what is interesting to me about having different artists and co-curators each year.

Giulia Blocal: I like how you incorporated the idea of assigning a different street artist as a co-curator for each edition in your documentary. They each have their own music theme and create a specific vibe, much like distinct chapters in a book. How did you come up with this idea? Also, do you have a favorite curatorship and which curatorship resonated most with the public?

Kristina Borhes: My favorite, mmh? I like all of them. I love every direction that the festival has taken. Actually, I really love even the new direction, which combines all the stuff, without associate artists. But if we talk about my personal preferences, that’s definitely Brad Downey’s year. That was 2018 and he basically almost broke everyone. But yes, that’s definitely my favorite.

Giulia Blocal: And the public’s favorite?

David Demougeot: Well, it’s always hard to talk about the public, because you have a lot of different audiences and different sociological ways to use the public space. But we had a lot of good feedback the year with Hyuro, and also when we worked with Eltono, as he is a really engaged and really social artist, he talks a lot with the people.

Giulia Blocal: David, in the movie it’s said that one of the festival’s goals is to build bridges between artists, their art, and people’s daily lives. Can you share specific instances where this connection had a powerful or transformative impact?

David Demougeot: I think about Anaïs Florin’s project, what she did with the gardeners. She worked in a huge gardening area that was going to be destroyed to build new houses. She visited the festival twice, she had a lot of interactions, and she is an artist but also an activist, so she spoke the same language as the people that are fighting against this building project. And this made a kind of community around it. The artwork is used to explain the fight of the people, while the zine we published on that occasion is on their table every time they do a meeting. It’s also interesting when the artwork is not a bridge between the artist and the people, but it’s a bridge between people; this is very interesting for me, because I’m not really a fan of art, I mean I’m not really interested in artists as, you know, the artist as a crazy interesting people. To me, some artists are crazy interesting people, but that’s not what is interesting in art. What is interesting in art is the change it can provide in people’s minds. Art creates something between people and, for me, that’s kind of magical. It’s something that politics really can’t do sometimes. So, yeah, I was really happy with this kind of project.

Giulia Blocal: The film showcases Bien Urbain as a benchmark, incorporating discussions about street art beyond the festival itself, through insights from experts like Vittorio Parisi and Raphael Schacter. How did you decide whom to interview and include in the documentary?

Kristina Borhes: Yes, that’s a really important thing, because we wanted different distances, you know, if the festival is a subject you need to have different perceptions, different distances. So first of all, we wanted to talk with the team, that’s the most obvious, the festival team, they know what they do and we can hear why they’re doing it. Then, you have the artists, the co-curators and the associate artists, who are kind of in between, they are artists but then they work with Bien Urbain, they cooperate with the team. Then, you have the artists that are significant to the festival, they can tell why for them it is important, why for them it was experimental or innovative to work at Bien Urbain. Finally, we always try to have a perception from the outside. Raphael Schacter is an amazing writer and curator, sometimes I disagree with his ideas, but I really respect him because he has a really broad idea of this culture in different ways. He’s one of the best. And he was in Besançon, he knows Bien Urbain pretty well because he took part in the conferences in different years, so he knows about the festival not just from outside, but he actually was there. Vittorio Parisi also was there, and he has a very interesting perspective that I wanted to hear. He wrote this article about the death of street art, and that was something that interested me, because Bien Urbain started in 2011, which is the year when more or less everyone started to say that street art is dead. I believe that’s not a coincidence, that’s actually really important, that’s really why they do it in a different way. So the choice was obvious for us.

Giulia Blocal: David mentioned in the movie that one of the festival’s objectives is to spark reactions and discussions in the public. What kind of reactions did you witness after screening the documentary in Besançon?

Kristina Borhes: It’s always super stressful to show the movie about a city in the city where it was made. Because people are part of it, it’s something that’s close to them. You know I always treat the city as a person, because each city has its own personality, and Besançon is really very nice and kind, and the people there are also super supportive. One of the reactions was that they were so humble, but also like “Oh, but it’s about our city,” they were genuinely surprised that we did a movie about their city, they were actually thanking us for it. Because it’s not like you will do something about New York.

David Demougeot: Also, people realized that it’s not just about doing something beautiful, because most of the people in every city, when they see art in the city, they say it’s beautiful or it’s not, and that’s completely fair, they don’t have to go further, so when they look at the movie, most of the people discovered that it was more complex than that. They realized that it’s not only about producing murals, because in Besançon, the way that everybody sees it, it’s that it’s a mural festival, because murals are big, so that’s what is most visible to people. But many projects we did were ephemeral and many people just found out about them by watching this movie.

Kristina Borhes: This reminded me that there was a nice gentleman in the public who was so emotional during the screening, and then he thanked us because he realized that he hasn’t seen a lot of these projects and there’s no possibility to have them back, because they were ephemeral, but they can be seen in this film, or in photos. That was nice.

Giulia Blocal: Now I want to know what reactions the movie has sparked in this audience! Do you want to say something to Kristina and David, or do you have any questions?

Question #1: First of all, Kristina and Nazar, thank you very much for the great film. Also, David, thank you very much for this stuff and these narratives. I would like to ask you about going illegally, you mentioned it in the movie, so how was the reaction of the people, and of the municipality?

David Demougeot: It depends, again, on which people we talk about. I mean, the municipality doesn’t care because often they don’t see it. Anyway, it’s not about illegality to me, it’s about emancipation: to be able to do things without thinking if it’s legal or not, but if it’s good or not. You can feel it when you work with the artist and when you see them working. We’re not really punk, hardcore, we take care of what we do. We are not really the vandals we have seen in many graffiti movies these days, we are not into that energy. So for example Brad Downey’s interventions on billboards, that was unsanctioned and we did it on a Sunday morning, because we knew there weren’t that many people around, the street was super quiet. And after the intervention, we cleaned everything. Because it was a performance, it was made for the video, not for lasting nor for vandalizing the city. So after photos were taken, we began to clean, and realized that it was super hard to clean, it took us hours. Eventually the police came, and asked us “What are you doing?” and we were like “Oh, we are cleaning. We are neighbors, we saw it has been trashed and we wanted to clean it.” And the policeman said: “Good job, good guys” and they were amazed at what great citizens we were. So it’s illegal, but it’s not… What is really interesting is that when any artist of the festival painted with a spray can and a hoodie, the police came every time, even if they had the permission. So illegality is not really the point, it’s what people think is illegal or not. And this is really easy to see when you organize this kind of project. Also with Jordan Sailer, we organized a workshop of adbusting: there were 15 people going around the city, opening the billboards and putting artworks in them. It all happened during the day, and it didn’t look like graffiti, so it created no problem. But if you go around the city with a spraycan in your hand, the police will come by really fast. So, yeah, the point is really not about illegality or not, it’s what people have in mind.

Question #2: Well, thanks for the film. It was lovely. I have a question for Kristina. You show all these lovely stories of all these artworks. I’m actually quite curious when you show this film to the artists, which reaction or which response from which artist stuck with you the most?

Kristina Borhes: Oh, I don’t even know. Because I have quite a good relationship with most of the artists in the movie, so even if they didn’t like it, I doubt that they will tell me. In general, I think not about this movie, but with our artist portraits, we did the portrait of an Ukrainian artist who’s absolutely not famous, not even in Ukraine. He’s a guy who works in construction, and graffiti for him is really a spiritual thing, it’s really something special. So it was quite hard for me to film, not to interrupt his process, but then, in the end, the movie turned out beautiful and he was super amazed that someone went to his city to document his work, he even showed the movie to his father, he was really proud that someone paid some attention to his work.

David Demougeot: Still about reactions, as you’ve seen in the movie, we provoked quite some reactions from anarchist groups who pasted posters against the festival, and that was super hard, but also super interesting. So if you have any negative feedback, please let me know, because it really helps to grow.

Question #3: First of all, I really want to thank you for making this film. It’s so nice to see the organizer’s perspective in such a movie. Usually, it’s just the artist being followed and here you really see also the role played by the organization, in being sort of the extension of the artist within the city. Like you said earlier, we are the experts of the city, artists are the experts of the art, and together we create something special. And I think it’s a real privilege, as an organization, to have such a documentary made about you. It shows not only what you’re doing, but also what you were doing, and how it evolved over time. You can see you’re reinventing the organization and the festival. So I was wondering, after you saw this film, did you change anything about the organization or did you get a better understanding of what you were doing?

David Demougeot: During the process of the movie, I was really in a mid-life crisis and really not sure that what we do is interesting. So, to be honest, it was quite hard for me to do all the process of this. And even if the movie didn’t change what we do, it helps a lot to say some words on what we do, because we don’t do a lot of interviews and we don’t get to talk about what we do, we just do it. For example, my colleague says so many good things in the movie, and we’ve worked together for 8 years but we’ve never talked about this stuff. So, this is important.

Enjoy my reel about the festival and stay tuned for the round up article!