If you’ve been following my monthly newsletter, you know I often reflect on how street art festivals can stay true to their roots while navigating an increasingly compromised system. At Blind Walls Film Fest 2025, I had the chance to moderate a panel on this very subject, bringing my questions to some of the most uncompromising curators in the field—especially one who not only pioneered the street art festival format in Italy but also shut it down with the same radical vision, in an act of artistic integrity.

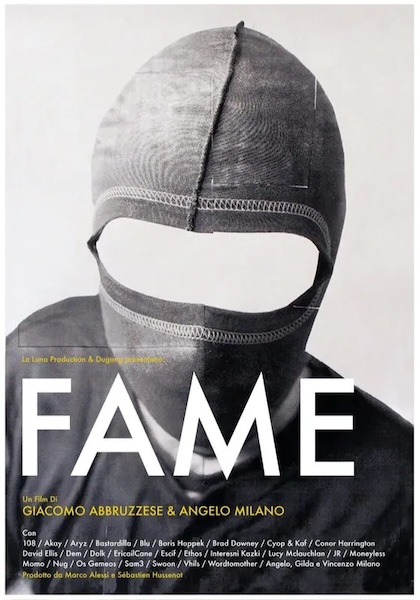

I’m talking about Angelo Milano, whose experience with the FAME Festival was at the heart of the documentary we watched just before the panel—a film that went on to win the festival’s top award.

Angelo Milano was joined by Daniel Claessens, artistic director of Rotterdam’s ALL CAPS Festival (formerly POW! WOW! Rotterdam), a festival that has evolved into a major event backed by sponsors and institutions, and street artist Pink Painter, who also has extensive experience in the production of the street art festival Crystal Ship in Ostend, Belgium.

Together, we delved into themes of autonomy, institutionalization, and artistic integrity. The conversation was too thought-provoking to remain confined to the stage of Chassé Cinema in Breda, so I wanted to share it with you. Enjoy!

Giulia Blocal: In the movie, we saw how much the artists loved being in Grottaglie, so my first question to Angelo is: What’s your mom’s signature dish?

Angelo Milano: It’s fava bean purée with chicory. It’s a very local recipe, so if any of you have been to Puglia, you’ve probably tried it—but not as good as my mom’s.

Giulia Blocal: Let’s start from the beginning—you were undoubtedly a pioneer, and FAME paved the way for many street art festivals across Europe. At the time, the only existing festival was Nuart in Norway, while Pictures on Walls in London was introducing a DIY screen-printing approach, opening up a new alternative market outside traditional contemporary art collecting. Was there any particular experience, in Italy or abroad, that influenced your initial vision? Did you draw inspiration from anything?

Angelo Milano: How can I answer this without sounding arrogant? No.

Giulia Blocal: FAME was radical also because the artworks were created spontaneously and unsanctioned, without asking for permission. How important was this aspect for you?

Angelo Milano: I’d say it was really the only important aspect. We needed to do it as a form of communication—it was an urge. You don’t ask for permission before speaking your mind, unless you’re polite, which I’ve never been.

Giulia Blocal: Daniel, let’s go back to the early days with you as well—you come from graffiti, so you know that world of unsanctioned creation, illegality, and painting without permission very well. Now, you run a highly successful festival in Rotterdam, which attracts major sponsors and is embraced by institutions. But what still remains from your past experience? How do you preserve the rawness, the roughness, the rebellious nature of graffiti in a structured festival setting? What do you actively do to stay authentic and honor the spirit of street art’s origins?

Daniel Claessens: Okay, that’s a lot of questions to answer. First of all, I really loved the movie—I didn’t know about the festival before. And yes, at ALL CAPS, we now have licenses and permissions, but there’s a small part of the program where we don’t. We always work with one, two, or sometimes three intervention artists who just go out and find a spot for their installations. So that’s the only part that’s still illegal.

Giulia Blocal (to Pink Painter): I want to circle back to this idea with you as well. In your current work, what’s the balance between commissioned and spontaneous pieces? Sanctioned and unsanctioned? Do you feel that your unsanctioned work differs from your commissioned work? In what ways? Does working without permission change your approach, your mindset, or even the final outcome? Or do you see it all as part of the same practice?

Pink Painter: Well, I think they’re completely different. My job is actually very legal—I do a lot of mural work, but it’s usually for big companies, so of course, everything is in place. I also do a lot of logo work. I think they’re really two different things; I’m not even sure you can call it street art anymore. I always say, “I paint walls.” I’m not really a street artist—I’m just a painter. Sometimes I’m an artist, but a lot of the time, I just paint what I have to paint.

Angelo Milano: To be fair, I don’t think it’s about being legal or illegal. It’s more about whether you have something to say or not. If it’s legal, it’s safer for you—good for you. I mean, the real risk is when it becomes purely decorative, losing its purpose as a form of communication. Decoration is just something you walk past, a brief visual relief, and then you go home without thinking too much. That’s what makes it dangerous.

Giulia Blocal: Yes, like wallpaper. Today’s festivals are regulated and curated spaces, turning street art into a tool for urban decoration. But the real issue isn’t about asking for permission—it’s about how something that started as an underground movement was swallowed by the mainstream. So, who do you think is to blame, and how did it happen?

Angelo Milano: Artists.

Giulia Blocal: Why?

Angelo Milano: Because artists are all the same—they all want money and fame. Their practice is driven by ego, nothing more. And not only that, my friends, but let me be very honest about it: have you ever noticed that every artist, when they paint a face, paints their own face? Even the abstract ones paint themselves. That’s just how it is—artists are all about their ego, climbing the fame ladder. They don’t care about anything else. Sorry, but what do they actually do? They’re sheep. We all are, in some way. We can all be seduced by money and these things. The contradiction, in this case, is that this genre—this movement, if you want to call it that—was, at some point, self-sustaining. We were doing our own thing, without asking for permission, without seeking support, without shaking hands with politicians. We sold our work on our own terms, at prices that made sure no power dynamic was involved. Normal people could buy a print for their home and feel good about supporting artists who actually needed it. It wasn’t about hoarding money or building empires. I don’t know if I’m making any sense. But yeah, I’m not saying corporations are good—I hate them all—but we’re all guilty of something, I guess.

Daniel Claessens: I’d like to think we haven’t sold our souls yet—to big corporations or for big money. We try to work in neighborhoods that usually make the news for stabbings or shootings. Then we go there, bring people in, and they say, “Oh, I didn’t know normal people lived here.” So, we try to find a balance—making art, making it look good, working with people, and doing it for the people. And of course, we do need some money. We ensure fair pay. But I do miss the times when you could just reach out to an artist and say, “Hey, do you want to come and join us?” And they’d simply say, “Yeah.” Now, I think half the artists we invite respond with, “Yeah… so what’s your budget?”

Pink Painter: Well, as an artist, I can answer that. For me personally, I just want to be outside on a lift, painting a wall. But I also like to have a home and make a living. So yeah, balancing those two things is what matters most to me. Whether it’s real art or not—I’ll leave that for others to decide. As long as I’m out there with a brush in my hand and someone is paying me for it, that’s fine by me.

Angelo Milano: Yeah, but I’m not criticizing this. I think you’re absolutely right, and it’s beautiful. I wish you the best of luck—keep doing this forever so you’re not enslaved by some other shitty job. But what I’m saying is: things moved so fast, and they got corrupted just as quickly. This was a real chance we had—it was truly authentic back in the day. Could it have gone on forever without becoming commercial? Because what happened is that it was corrupted. At some point, some of the artists you saw in this movie smelled money, fame, and prestige, and they all jumped on a bigger boat. There was a very specific moment, in 2007 or 2008, when some artists were left behind on a smaller boat, and they started to panic. So they all scrambled to find a way to survive—to jump on the bigger boat, you know? That’s when I think we lost the opportunity to truly be free, to say whatever we wanted. And we can see it clearly now. I keep meeting my artist friends that when we talk in person, they’re all about Palestinian-Israeli shit, Israeli shit, Israeli shit, and then they can’t say a single word because all the people financing them are actually Israeli or whatever, you know. And this is so sickening. It’s the saddest thing ever. Because back in the day, we would say whatever we wanted. Now? I can name 100 artists who, when it was about Ukraine, were all “Oh, Russia is evil!” and waving blue-and-yellow flags. But now, with Palestine, they say nothing. And that’s just another fucking sign that they’re all corrupted. It’s horrible.

Giulia Blocal: The film also shows the shift from your initial enthusiasm to final disappointment, when you realized that something spontaneous and genuine was being absorbed by the system. What was the most frustrating aspect of this process for you—on a personal level, I mean?

Angelo Milano: Personally, it was when I saw the festival being reduced to just a party—like that was all it was. I’d see my friends coming just for the party, for the music and dancing at the studio, and I felt like some of the spirit had been lost. At the same time, a lot of smaller festivals started to imitate what we were doing. And by imitate, I mean they were trying to do the same thing, but with public money and funding—and without any real content, you know? So, I wanted to avoid getting lost in this cacophony of similar things, where everything looks the same online, and people scroll through photos quickly on their phones without knowing what’s behind them. I think I felt disappointed, and still, in a way, it was a good thing. Anything we do is better when it’s alive. You have to know when it’s the right time to stop—because otherwise, it ends up under a glass dome, like some museum relic. It stops living, then it’s dead. So, it’s better to end it while it’s still alive. And the only reason we’re still talking about it now is because it ended when it needed to. If I had kept it going, it would have just turned into a money machine or whatever, and I would have had zero interest in it.

Giulia Blocal: Daniel, I have a frustration-based question for you as well. Is there something about today’s institutionalized street art scene that frustrates you, given your background? Something you wish were different?

Daniel Claessens: Of course, there’s a lot that frustrates me. For example, we try to work around censorship as much as possible—artistic freedom is very important to us. That’s what we push for, but there have been times when people wanted to remove a piece.

Giulia Blocal: Oh yes, I remember, I was there. That was Eneri’s pixação, right? [I wrote about it in my monthly newsletter as well, Ed. note]

Daniel Claessens: Yeah, yeah. We do our best to let artists create what they want. That’s one of the biggest challenges for us as a festival. The second thing that frustrates me—or that I absolutely hate—is when we’re told we have to do participatory walls. The idea that people on the street should decide or provide input for the artist. And then it’s like, “Yeah, my grandmother’s goldfish… and my favorite color is pink.” And suddenly, they expect the artist to paint a pink goldfish or whatever they want. It’s hard for us to explain: No, this is the artist. You agreed on their style, and now you have to trust the process and let them create what they create.

Giulia Blocal (to Pink Painter): And what about you? Is there something about today’s institutionalized street art scene that frustrates you?

Pink Painter: I think one thing that’s still very visible is the issue of gender equality. There are still far more male artists, so that’s something we need to be aware of.

Giulia Blocal: Angelo, do you think there’s still room today for experiences like FAME, or has street art become irreversibly part of the system? And since you’re still active in the field—though with different projects, from your gallery Studio Cromie to the Fuckups Festival—what are the rules you play by now? How do you navigate the system while staying true to yourself?

Angelo Milano: Okay, it’s not that street art is corrupt. The problem is that it’s boring. It’s super boring. Maybe I’m jaded because it’s been a long, long time, but I don’t see any meaning in it anymore, any purpose. It has failed dramatically—or almost. There are a few sparks here and there, but nothing that really moves me. It’s just not worth it. Every other modern cultural movement had its time, right? And then it stopped. That’s normal. Think about it like this—imagine a selected discography from the ‘80s. Now, what if disco music had kept going unchanged until today, without any rival? Imagine it was still just disco in 1995, in 2000, the same thing over and over. Wouldn’t that be extremely boring? So why does street art keep going endlessly for no fucking reason? We should just let it die. And maybe in 20 years, something else will take its place. The problem is—and I don’t want to sound cynical—but since it’s a product, people are making a living from it. So it has to keep going. But to me, it’s more about people getting a job than actually doing something meaningful. And honestly—and I don’t mean this against you guys or anyone in particular—all the rhetoric about inclusion and community? It’s all bullshit. I’ve seen this art in so many abandoned, forgotten districts, and what does it actually do? People are living in horrible houses with no electricity, no water—but hey, there’s a beautiful painting outside. What’s the point? Maybe my kid can smile for a minute, maybe it’s nice to see something inspiring—but the real problem is something else entirely. Instead of wasting money on this stuff, let’s put it toward something actually useful. Or, if you really believe in it, take responsibility—do it with your own money, make a profit for yourself and the artist. Otherwise, what’s the point? Sorry.

Giulia Blocal: But what are your rules now, with the new projects you’re working on?

Angelo Milano: I don’t have rules. I’m just doing things honestly, in my own time, and I don’t ask for support from anyone. I don’t ask for permission from anyone. I keep doing what feels relevant to me and myself only, because I’m selfish too and I just want to be content and happy. I live in a very remote part of the world, and I want people to come visit because I love Grottaglie, even though I can’t deal with how boring it is. So my only rule is to entertain myself all the time and make just enough money to never have to think about money—without falling into the trap of making too much.

Giulia Blocal: Do we have any questions from the audience? Over there? Go ahead.

Question #1: Hi. Is it in your nature to document everything? Because normally, you just start painting, and after a few years, you think: Oh, shit, I forgot to document this.

Angelo Milano: That’s a fun question. First of all, those videos were not shot with the intention of documenting, of making a documentary film. The videos you see in the movie—some animations, some clips, some things with music—were made on the go while we were painting, so we could upload them to a blog and invite people in. The festival’s production ran from April to September. While we were working on everything, I was documenting it all through these clips, uploading them online for people to see, get curious, and hopefully come visit us in September to support what we were doing. Then, years later, a friend of mine—whom I met again after a long time (and later, when I went back through the archives, I even found a photo of us together, drunk at a party, so apparently we had already known each other)—asked me to make a movie about it. He managed to get me to sit in a chair for about a month to edit the whole thing. But the material had been recorded for other purposes, not for making a movie. Funnily enough, I didn’t learn from that experience. And now I’m making another movie—which, again, I documented completely by chance. In fact, the entire first part of the film is vertical because I was originally just filming Instagram stories. Then, at some point, it turned into a movie, and I ended up performing in it. So yeah, I just stumbled into making a film, but I don’t document with the intention of creating movies. It’s the movies that happen.

Question #2: In the movie, I saw a lot of joy—you had so much fun doing this. But hearing you now, sorry for saying this, you sound slightly sarcastic about the whole situation. Do you still have a project that makes your heart race the way it did back then, or are you completely fed up with it?

Angelo Milano: I’m fed up with the situation, not with the movie. I made this movie so that we could stop talking about it. It was a milestone for me, a way to close that chapter and move on to something new, rather than being the guy from the festival. I mean, I have a lot of projects that keep me very, very happy. Do you want me to tell you about a few? My favorite right now is this collaboration with Rosario Pedone. He’s a 60-year-old guy from Grottaglie who I used to be friends with a long time ago. Weirdly enough, he was the town fool. He’d walk around town while people bullied him—spitting on him, insulting him, throwing rocks. But back then, we became friends because, strangely, he was into punk rock. This guy knows punk bands that are very obscure, even hard to find information about. He used to come to my place because he heard I was playing in a band, and he’d ask me to download records for him. That’s how we became friends—he felt safe talking to me because we had something in common, you know? Fast forward to 2020, post-pandemic, whatever. He comes out of lockdown as a painter. Suddenly, he’s showing up at the bar with all these paintings in his hands, trying to sell them to the same people who bully him. It’s a masterpiece of bravery and self-determination, something I’ve never seen in any other artist. This guy stepped out of his house, alone, against everybody, trying to sell his paintings. So I helped him. I bought some myself, and then I force-fed the rest to people at the bar. And then—just casually, without thinking—I told him, “One day, we should do an auction with your paintings.” He left without even replying. I’m sure he didn’t even know what an auction was. But the next day, he showed up at my place with a pile of paintings and said, “I’m ready for the auction.” I thought we’d take time to organize it properly, but no—he was ready now. So I had to improvise. I jumped on Instagram, launched the auction, and suddenly, everyone freaked out. They all bought his paintings. It was wild—big collectors, serious artists, crazy money. Now there are homes with Picasso paintings hanging next to Rosario Pedone paintings. It’s unbelievable. And sure, that’s the flashy side of it. But the real story is that his life changed. He’s no longer the town joke—now he’s Maestro Pedone. People greet him with respect. And it’s beautiful. I’m actually making a movie about this now. That’s the project keeping me most engaged. Then, as Giulia mentioned, there’s Fuckups Festival, which reminds me a bit of the old FAME atmosphere. It’s all artists who are terrible at promoting themselves—either because they’re incapable, lazy, or just unwilling to keep up with the speed of social media. They create amazing work, but they have no idea how to put it out there. So I gathered around 30 of them and created this collective festival. The performances are insane, the art is beautiful, and they sell their own work—they get all the money from it. I just charge an entry ticket for the music concert at the end of the day, which they also play at. It’s an amazing experience. There’s no money involved beyond what they earn directly. And the best part is that, finally, they have a space to showcase their work. It’s horizontal, it’s collaborative, and it feels like a family. They end up working together, building a network. It’s called Fuckups because they don’t fit into the way things work today.

Question #3: What do you think about this movie yourself? I mean, it was quite a long time ago for you. How do you see it now?

Angelo Milano: I try not to watch it anymore—I stay out of the cinema as much as I can. But I think it works well for everyone. If it had been entirely up to me, I would have made a more technical film, one that focused on the things that used to bother me at the time. But looking at it now, I think we made a film that even a 95-year-old lady could understand. So in that sense, I think it’s kind of fun. The music is great, it keeps people entertained. It’s just one hour—after that, it might get boring. But it’s fine. I’m okay with it. It had a beautiful life. It’s been eight years, and it’s still being screened, still traveling everywhere. And it’s taken me to a lot of places.

Question #4: From a filmmaker’s perspective, do you see value in documenting street art today? Or should we stop documenting it altogether?

Angelo Milano: Yes, please. But the problem isn’t the documentation—it’s the making. So yeah, let’s kill it. Let’s just be quiet for 20 years. Let’s put the brushes down for a moment. It’s time. Sorry.

Question #5: I promise you this is a question you’ve never been asked before, so I thought long and hard about it. Would you rather spend the rest of your life with wrinkly swimming pool hands or Cheetos fingers?

Angelo Milano: Cheetos fingers. You can still eat the cheese in the swimming pool.

Enjoy my vlog from Blind Walls Film Fest 2025!