‘Listen’, ‘Pss’, ‘Grr’. So many voices are coming out from the funnels hung on the ceiling that I can’t hear mine. Suddenly, everything is quiet for a few seconds, but even the silence –at this point- gets me muddled. Then, again, more voices are calling to me: ‘Look’, ‘Ehi’, ‘Pss’, ‘Woof’. Calls, bleary sounds, background noises that were scattered through the days of those people who used to live inside this very building, the psychiatric hospital of Santa Maria della Pietà in Rome.

Shut down after the Italian Mental Health Act of 1978 (the Basaglia Law), for more than 5 decades the mental asylum of Santa Maria della Pietà had been home to hundreds of patients, among whom the painter Gianfranco Baieri, who checked in voluntarily after attending the primary school at the hospital and who eventually spent his whole life in here, working as an hospital attendant, and dying just a few days before the closure of the asylum.

Another painter that was interned here is Oreste Fernando Nannetti, the leader of the Art Brut movement, who notoriously carved a 180-meter long mural using only his belt buckle on a wall at the Volterra mental asylum, where he was moved after a short stay at Santa Maria della Pietà.

The complex of Santa Maria della Pietà is huge, extending over 20,000 sqm or so. Huge as the fear of “the crazy ones, the misfits and rebels, the ones who see things differently” (here I go, quoting Steve Jobs ☺ ).

Nowadays, one pavillon of the former mental asylum houses the Museo Laboratorio della Mente (curated by the Local Health Authority Roma 1), where visitors can travel through the history of the hospital and of those who lived inside it, by following an interactive and extremely empathic itinerary. You can lean on a table and ‘hear the voices’ or rock on the chair reproducing the obsessional movement so common among these patients; you can see the machineries for the shock treatments, the forbidden forks hung on the wall, the funnels that –dangling from the ceiling- represent oppression and brainwashing.

There is the restraint room, tiny and cold, with just one camp bed on which the obligatory straightjacket is lying (“they kept us tied, like sacks” says the narrator of the installation in the next room “especially children, as they were always making a mess, creating problems”). There is a pharmacy where ampoules and poisons are displayed inside an ancient, wooden cupboard, the doctor’s office and the bundle room, where patients left their civvies, which ended up rotting in here, growing cobwebs.

A room with an unusual perspectival structure makes us realize that our brain prefers to see different people as out-of-proportion rather then change the visual patterns it is used to following, and so change our idea of the structure of the room. This unveils the unconscious mechanism that is behind our preconceptions.

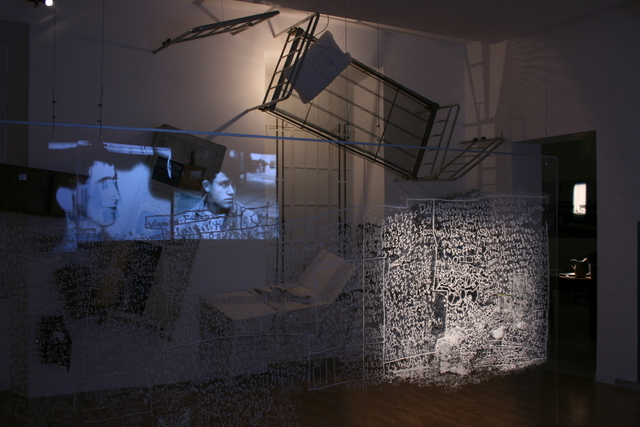

More interactive installations make us perceive time, memory, speech or reality in twisted ways, through suggestions that push us into different, out-of-sync dimensions, where everything is there to be reinterpreted and re-evaluated, but without knowning how, or being able to master the appropriate methods. Logic, perspective, speech and rationality are useless if we don’t have methods to interpretate them: without methods we feel lost, thrown into a world we don’t understand.