The People’s Republic of Bulgaria was the official name of the Bulgarian socialist republic that existed from 1946 to 1990. The Bulgarian Communist Party was ruling the country and the prime minister was Georgi Dimitrov until 1949, then Valko Chervenkov and Todor Zhivkov after him. I found the Bulgarian socialist past an excellent ‘fil-rouge’ to dig into Sofia’s architecture, art and monuments, from the city centre to the Museum of Socialist Art and the several areas in the outskirts built according to the standards of socialist architecture to accommodate the multitude of people who came from the countryside to work in the new factories that the Party wanted.

The People’s Republic of Bulgaria was the official name of the Bulgarian socialist republic that existed from 1946 to 1990. The Bulgarian Communist Party was ruling the country and the prime minister was Georgi Dimitrov until 1949, then Valko Chervenkov and Todor Zhivkov after him. I found the Bulgarian socialist past an excellent ‘fil-rouge’ to dig into Sofia’s architecture, art and monuments, from the city centre to the Museum of Socialist Art and the several areas in the outskirts built according to the standards of socialist architecture to accommodate the multitude of people who came from the countryside to work in the new factories that the Party wanted.

Communist regime’s tracks in Sofia > THE TOUR OF COMMUNIST SOFIA

As you know, I’m not a guided-tour kind of traveller, but everybody told me that the walking tours organized by ‘365: Free Sofia Tour’ are informative and entertaining and so I thought I would give them a try. And I found myself on the Communist tour, which lasts 3½ hours and covers almost all the city centre and 45 years of Bulgarian history.

During the tour we discussed several different aspects of the Communist regime in Bulgaria. In front of the tiny church of Saint Nicholas Mirlikiysky (a family chapel from the 13th century on Kaloyan street), I learned that during communism religion wasn’t actually banned –as I had thought- but people could normally go to church, although they might get in trouble with the security police later.

The security police were in charge of crafting a suitable image of Bulgaria for the foreign media and of filtering the news broadcast in Bulgaria; it was a powerful and very conspicuous group of spies serving as the eyes of the Party. A joke was enough to get you suspected, interrogated behind a small, nondescript door located in a hidden alley (ulitsa Malko Tarnovo), and eventually beaten to death or sent to a labour camp. The security police headquarters was connected to a network of underground tunnels and bunkers whose mapping is still top-secret, although it is rumoured that some of these tunnels have been reconverted as part of Sofia’s subway network. (I’ve found a video of some brave urban explorers letting themselves down into these tunnels).

On Prince Alexander of Battenberg square we imagined the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum, which was built here in 1949 in a record time of just 6 days to hold the embalmed body of the communist leader, and which was later destroyed in 1999 because it stood for Bulgaria’s repressive past. This was also the place where national celebrations were held and parades marched past. We discussed the opposition to the regime while we visited the nearby Krystal Park, where the first democratic protest was held in 1989, a demonstration that began as an environmental march but soon turned into the political rally that is considered the spark that eventually brought about the deposition of Zhivkov and, one year later, the end of the Communist regime.

Surprisingly, a couple of buildings were a pretext for considering also some positive aspects of the Bulgarian communist period, such as the free education system, which decreased illiteracy by 80%, and the importance given to sports, which led to a generation of exceptional athletes whose records, in some cases, are still unbeaten.

We also went to two of the weirdest monuments in Sofia which I had walked past, puzzled, the day before: the monument celebrating ‘1300 years of Bulgaria’ (the ugliest monument in Bulgaria, according to popular opinion), which represents the past, the present and the future of Bulgaria, and the Monument to the Soviet Army, created as a symbol of gratitude to the Soviet Red Army for helping Bulgaria during WW2; at the top of it, the female worker advancing together with a male worker and the soldier were an occasion to learn that, during communism, for the first time in Bulgaria women were allowed to work and they even received an equal wage.

the ‘1300 years of Bulgaria’ monument

the monument of the soviet army

The side façade of this latter monument has, on multiple occasions, been turned into canvas for anonymous political statements: in June 2011 the Soviet Army soldiers were transformed into popular American superheroes and cartoon characters, in August 2013 the monument was pink-washed in honor of the anniversary of the Prague spring, while in February 2014 it was painted in the national colors of Ukraine in support of the Ukrainian Revolution.

Facing the National Palace of Culture -a huge complex wanted by Zhivkov’s daughter Lyudmila Zhivkova and still operating as a multifunctional cultural center- we talked about the role of the arts during the regime, which of course was to serve communist propaganda.

The tour could not have ended in a more appropriate spot: in front of a fragment of the Berlin wall, whose fall symbolized the fall of communism all around Europe.

Communist regime’s tracks in Sofia > THE MUSEUM OF SOCIALIST ART

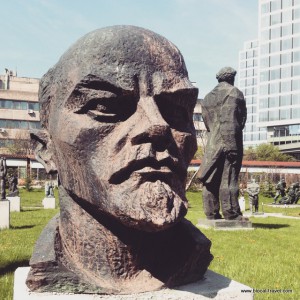

On the morning of that same day I also had a Communist tour by myself, through Sofia’s outskirts, starting from the Museum of Socialist Art, which unfortunately happened to be changing its exhibition on that day but, at least, they let me visit the outdoor sculpture gallery.

In the sculpture park of the museum I saw both the large statue of Lenin that once stood in the centre of Nozavisimost Square, where the statue of Saint Sofia now is, and the red star that topped the socialist party headquarters on the same square.

The museum hosts artworks from the 1950s to the 1980s: portraits and sculptures of the former socialist leaders, not only of Bulgaria but of the all Eastern bloc.

Communist regime’s tracks in Sofia > THE MLADOST DISTRICT

After visiting the Museum of Socialist Art I headed to Mladost, a district in the southern outskirts of Sofia and one of those areas built during the socialist regime to accommodate the multitude of people who came from the Bulgarian countryside to work in the nascent industrial sector.

While a few of them were accommodated in downtown Sofia, where former owners were forced to share their lodgings with the newcomers by splitting big apartments into smaller flats, many other people moved into those huge concrete constructions characterizing the Soviet outskirts all over Eastern Europe, the so-called ‘horizontal skyscrapers’.

Wandering around this concrete jungle was one of the strongest experiences of my trip. But, to be honest, Sofia’s soviet outskirts had already gotten to me when the airplane flew over them, and I saw blocks upon blocks of concrete buildings stretching all around the town I couldn’t wait to explore.

PEEK THROUGH | You find the charm of Sofia in my video “4 days in Sofia…in 40 seconds“