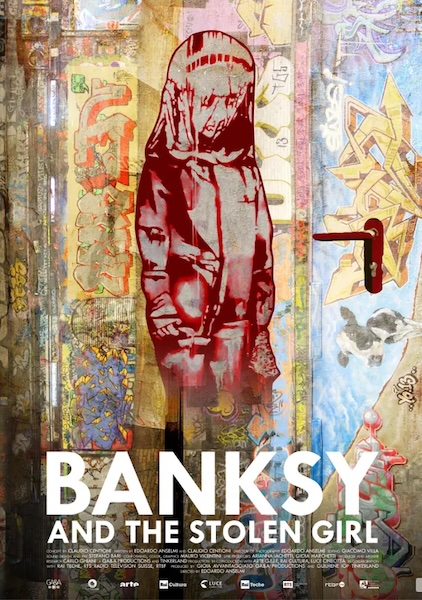

While preparing a presentation on the movie Banksy and the Stolen Girl (2023) for the audience at Blind Walls Film Fest 2025, I wrote this article exploring its themes, from street art ownership to its role in public space.

Banksy and the Stolen Girl, directed by Edoardo Anselmi, delves into the enigmatic theft of an emergency exit door from the Bataclan theatre in Paris—a door that bore Banksy’s mural The Sad Girl. Created in June 2018, this stencil-based artwork was a tribute to the victims of the November 2015 terrorist attacks.

As with much of Banksy’s work, its technique was deceptively simple, but its message was deeply powerful. Almost instantly, The Sad Girl took on a symbolic role, functioning as an unspoken memorial for a collective tragedy.

Yet beyond the specific crime at its center, the film raises broader questions about street art and its paradoxes. Who truly owns a piece of art created in public space, often without permission, yet imbued with cultural significance? Who has the right to remove, preserve, or sell it?

Street art, by its nature, exists outside traditional frameworks of ownership—it is site-specific, ephemeral, and meant for public engagement. And yet, as its value in the art market skyrockets, it is increasingly treated as a commodity, subject to theft, auction, and legal disputes.

The theft of The Sad Girl is emblematic of the contradictions embedded in both Banksy’s phenomenon and the contemporary art world at large. Works that were created illegally are now worth millions, protected by law enforcement, and debated in courtrooms. Police investigate their theft as if they were sanctioned cultural heritage, even when their very creation once defied legal boundaries. The film highlights the growing tension between street art’s original intent and the structures now forming around it—raising urgent legal, ethical, and philosophical dilemmas.

Banksy and the Stolen Girl is not just about a missing artwork. It’s about the ever-evolving nature of street art: its fleeting existence, its ties to urban space, and the complex dynamics that emerge when an anti-establishment art form collides with the art market.

When a work meant to engage with the public is stripped from its original setting, does it lose its essence?

And in attempting to preserve street art, are we also erasing the very qualities that make it so compelling—its impermanence, its dialogue with the city, and its raw, unfiltered presence in the streets?

Street Art is Site-Specific

One of the defining characteristics of street art is its deep connection to the space it inhabits. The power of an artwork often lies not just in its imagery but in its relationship with its surroundings. The Sad Girl was painted on the very door through which concertgoers had escaped on the night of the November 2015 terrorist attack—a detail that gave the piece a profound emotional and historical weight. It wasn’t just an image; it was an integral part of the site’s memory, a silent yet powerful tribute.

This site-specific nature is fundamental to street art, yet it is frequently disregarded when artworks are removed from their original locations. Banksy’s pieces, in particular, are often targeted due to their immense market value, leading to a paradox where street art—originally meant to exist within and interact with the urban landscape—is uprooted and turned into a commodity.

The film raises an essential ethical question: What happens when a work created for a specific place is taken from that context?

Street art is often intended as a public gesture, meant to provoke thought or act as a communal gift. When it is detached from its surroundings and placed in a private collection or a gallery, does it retain its meaning, or does it become something else entirely—an artifact rather than an active statement?

Banksy and the Stolen Girl underscores how the commodification of street art often undermines its very essence, transforming site-specific interventions into detached, decontextualized objects.

Street Art is Ephemeral

Another fundamental aspect of street art is its ephemerality. Unlike paintings housed in museums, which are carefully preserved for centuries, street art is meant to exist in a transient state—subject to time, weather, and the evolving layers of the urban landscape. Its impermanence is not a flaw but part of its very essence, contributing to its raw energy and urgency. By stealing or extracting a piece meant to fade naturally, we force it into a permanence it was never intended to have—stripping it of both its meaning and its original form.

For this reason, the problem with The Sad Girl’s disappearance isn’t that the artwork is no longer visible on the street. If it had been painted over, damaged by time, or naturally faded, it would have remained in harmony with the principles of street art—art that exists in a constant dialogue with the city, never meant to be frozen in time. Instead, it was forcibly removed, stolen not just from the wall but from the community it belonged to.

Street Art Belongs to Everyone

At the heart of this theft is the act of privatizing something that was intended as a public gift. The issue isn’t just that The Sad Girl is gone—it’s that someone decided to steal a piece of art that belonged to everyone. The mural had been created for the people, existing in public space as a form of shared expression. Taking it away for personal gain strips it of its meaning and distorts its purpose.

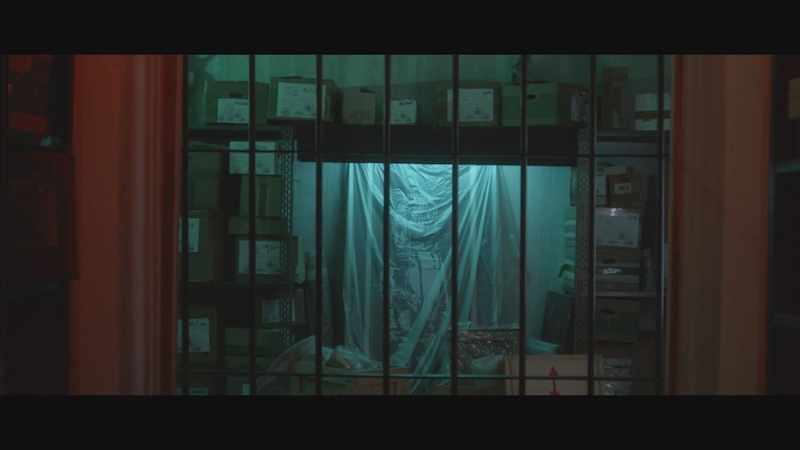

This is a recurring problem, particularly with Banksy’s works, which hold enormous financial value. When stolen pieces surface, they often appear on the dark web, where art traffickers attempt to sell them outside legal markets. Unlike authenticated artworks, which require a certificate of authenticity from Pest Control—the verification system Banksy established to counter this exact issue—his street pieces cannot be certified, as a way to discourage theft. Without this certification, legitimate collectors won’t touch them, forcing stolen Banksy works into underground networks of illicit sales -as shown in the movie.

The case of The Sad Girl is yet another example of how the commercialization of street art often clashes with its original intent. What was meant to be an ephemeral, site-specific statement turned into an object of financial speculation—removed from its community, stripped of its context, and reduced to a commodity for the highest bidder.

Banksy’s First and Second Paradox: Anti-Capitalist Art Worth Millions

One of the greatest contradictions surrounding Banksy’s work is that his pieces—often created illegally and loaded with anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist messages—are now worth millions. His murals critique gentrification, wealth disparity, and the commodification of art, yet they have become some of the most sought-after and expensive artworks on the market. Collectors, auction houses, and investors eagerly compete to acquire pieces that were never meant to be bought or sold.

This paradox is particularly striking because Banksy himself has repeatedly denounced the commercialization of his work. He has actively tried to prevent street pieces from being monetized by refusing to authenticate them through Pest Control. Yet the art market finds ways to circumvent this, with stolen or extracted works appearing in private collections or unauthorized exhibitions, detached from the urban landscape they were meant to inhabit.

The Sad Girl is just one more example of how the very system Banksy critiques has managed to absorb and exploit his art, reducing socially conscious street interventions to luxury commodities.

Banksy’s Third Paradox: Law Enforcement Protecting Illegal Art

Another irony that Banksy and the Stolen Girl highlights is how law enforcement mobilizes to safeguard illegal artworks.

The very institutions that, in theory, should be prosecuting vandalism are instead working to protect and recover pieces that were created illegally. Banksy’s works, despite their unauthorized nature, have been embraced as cultural heritage—leading to a bizarre situation where authorities chase down thieves not to remove unsanctioned street art, but to restore it to its original place.

The case of The Sad Girl takes this contradiction to another level. The film underscores how both French and Italian law enforcement agencies collaborated to track down the stolen artwork, conducting a cross-border investigation to retrieve a piece of art that, legally speaking, had no right to exist.

This raises the question: at what point does street art, an inherently rebellious and transient medium, become institutionalized? And if a work of street art is now something that governments protect and museums preserve, is it still street art?

Street Art and the Law

Street art, by its very nature, is often created without permission, directly challenging conventional notions of ownership and intellectual property. While copyright laws exist to safeguard an artist’s work from unauthorized reproduction or misuse, applying these protections to street art presents a series of contradictions. These works were not meant for private ownership; they were created as a public gift, a collective treasure. So how do we define and defend their integrity within a legal framework that was never designed for art that deliberately exists outside institutional boundaries?

The legal challenges surrounding Banksy’s work highlight these complexities. In cases like The Sad Girl, the crime is clear: theft. The same applies to a more recent incident in Peckham, London, where a Banksy stencil of a wolf on a satellite dish—part of his summer 2023 series featuring zoo animals—was stolen directly from its original location.

However, the legal landscape becomes murkier when the person removing a Banksy piece is the rightful owner of the surface it was painted on. This issue arose again last summer when another of Banksy’s animals, painted on a billboard, was taken down—not by thieves, but by the legal owner of the advertising space. Cases like this raise difficult questions: Does the property owner have the right to remove and sell the work? Or does the cultural significance of Banksy’s art transcend individual ownership?

These legal dilemmas are becoming more frequent as street art continues to gain commercial value. Yet fundamentally, these artworks were created to exist in public spaces, intended to engage with passersby rather than sit behind glass in a private collection.

The question remains: can something designed to be free and fleeting ever truly be protected by law?

The tension between street art’s rebellious, ephemeral spirit and the desire to protect it as civic property—owned by the community rather than individuals—highlights the limitations of current copyright laws. These laws were designed for permanent art forms, not for works meant to engage with public spaces, provoke thought, and sometimes fade away.

Community Ownership vs. Legal Ownership

In cases where a Banksy piece is removed and sold by the property owner—without theft or vandalism—the action is legally sound. But does legality always align with ethics? I would argue that it doesn’t. Street art doesn’t belong to the owner of the wall, door, or billboard it was painted on—it belongs to the community. It is a form of public expression, a shared cultural asset that was never meant to be privatized.

I see street art as a gift to the community, and removing it for profit feels like an act of theft—one that deprives the public of something that was meant to be freely experienced. Yet, at the same time, property owners have the legal right to determine what happens to their premises, including the artwork on them. This debate exposes a deep tension between legal property rights and communal ownership of public artworks. While the law protects individual ownership, many believe that street art, once created, enters the public domain and should be preserved as part of the shared urban fabric.

So who is the rightful owner of a street art piece?

Is it the person who legally owns the surface it was painted on? The public, who feel a collective connection to it? Or the artist, who never intended for it to be bought or sold in the first place?

This uncertainty is at the heart of Banksy and the Stolen Girl, a film that underscores how the fate of street art is often determined not by artistic intent, but by who controls the surface it was created on. But beyond the legal frameworks, the real question is about power, control, and who gets to decide the future of something that, from the moment it appeared, became a public treasure.

- Read also: “Been Enjoying Banksy’s London Safari – but who benefits from those street art pieces in the end?“ (This is the newsletter I sent on September 1st—if you enjoy street art editorials like this, subscribe here to receive them on the first of every month.)

For me, the greatest paradox in Banksy and the Stolen Girl is not just the contradictions surrounding street art ownership, but who ultimately articulates the most fundamental truth about it. The idea that street art belongs to everyone might seem obvious to the readers of this blog—yet, in reality, it is anything but. If it were universally accepted, there wouldn’t be a thriving market for stolen or extracted Banksy pieces, nor a constant tug-of-war over their rightful place.

What makes this paradox even more striking is that, in the film, this simple yet profound observation doesn’t come from an artist, an activist, or a cultural theorist—it comes from a policeman, someone whose job, in theory, is to combat unsanctioned street art. And yet, he is the only one who truly grasps what street art represents: a form of public expression that belongs to the community. Meanwhile, the thieves, dealers, and various other figures involved in the story see only economic value, focusing on profit rather than meaning.

Banksy and the Stolen Girl highlights how street art is more than just imagery—it is entangled in questions of access, belonging, and power. The real takeaway isn’t just about tracking a stolen artwork but about recognizing what is lost when street art is removed, whether by thieves, authorities, or the art market. This mural was not simply an object—it was part of a place, a moment, and a community. By shifting the focus from who owns the artwork to who it was meant for, we can understand that street art is never about possession, but about presence. And once it is taken away, something more than paint disappears.

- Watch also: My videos on Banksy’s London Zoo series: